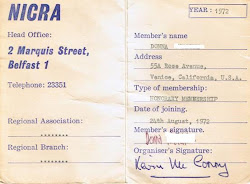

In June of 1972 I got on an airplane in Los Angeles and flew to Dublin, and then took a train to Belfast. I walked from the station to a small alleyway off a busy street in the centre of the city and rang the bell at Number 2, Marquis Street. The door was opened and I walked up two flights of bare, ageing stairs, passing two floors of light manufacturing workshops. On the top floor, I walked into a seedy office. The carpet was an indeterminate colour and was worn through in patches. A man called Kevin McCorry got up and asked me what I wanted.

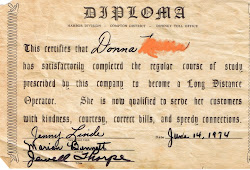

“I want to volunteer,” I said. He looked at me, not knowing what to make of this slight American girl, so determined to join the struggle. We talked for a bit and I told him what I felt I had to give to the organisation – mainly my willingness to do the donkey work.

“Do you want to start right now?” he asked me. And that is how I ended up working for the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association that summer.

I was studying sociology at UCLA and the field I had decided to concentrate on was Irish social history and politics. I had got quite a lot of help from a graduate student at the university called Seamus Thompson, who was from Belfast and who suggested that the best way to get to know the place was to go there. So I did.

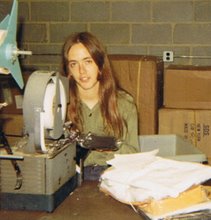

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) put me to work typing up reports and press releases, filing and doing errands. It didn’t matter to me that I could have been doing that kind of work in any office anywhere. It wasn’t any office anywhere. I was in the presence of History in the Making.

When I first arrived in Belfast, I stayed with Seamus Thompson and his parents. He was spending the summer doing research on his doctoral dissertation about the Protestant community of Northern Ireland.

He was a Protestant himself. His real name was Lawrence, but, as he had been born in the Republic of Ireland, the kids at his school gave him an Irish nickname that stuck. Anyone who knows anything about Northern Ireland knows that Protestants are not called Seamus (which is as Irish Catholic a name as you could imagine); and Catholics are not called Lawrence. I guess these conventions make it easier to know who to hate.

Seamus’s father was a retired minister, and he and his wife lived in a leafy upper middle-class area of the city across from Ormeau Park, just a short walk from Ian Paisley’s church. He was a quietly spoken man who was just that bit eccentric under his conventional veneer.

Every day at breakfast there would inevitably be one tomato or rasher of bacon or piece of toast left over.

“Does anyone want that tomato/rasher of bacon/piece of toast?” he would ask. We all would say no, but this was never the end of it. He would turn to me, “Won’t you have this tomato/rasher of bacon/piece of toast? Please do have it! Don’t you want it? No?” Then he would turn to Seamus. “You’ll have this tomato/rasher of bacon/piece of toast, won’t you? There’s only the one left! Are you sure you don’t want it? Sure? No?” Then he’d turn to his wife. “How about you? Won’t you have the last tomato/rasher of bacon/piece of toast? Do have it! Don’t you want it? No? Are you sure?” Eventually he would be convinced that no one else wanted it. “Well, if no one else wants it, I suppose I’ll have it!” he would say. And you could tell by the way he tucked into it that he had wanted it all along. This happened every morning. It was a ritual. If I was his wife I would have throttled him.

His mild, deferential nature extended to his politics as well as his breakfasts. He was a member of the then newly formed Alliance Party. It was composed of moderate unionists who sought to attract Catholics who were happy to remain in the United Kingdom, and Unionists who were happy to accommodate the civil rights demands of Nationalists. It went the way of all the moderate parties over the coming years. It sank without trace.

He was an innocent who couldn’t really take in the horror that was around him daily. He was only mildly annoyed that car theft had become so common that, as he didn’t have a garage at his house, he had had to rent one that was a full ten minute walk away. He owned a Ford Cortina and this made him particularly vulnerable, he was told, because Cortinas were the cars most often hijacked by the IRA for use as car bombs. Seamus’s father wondered why this should be so. “It’s probably because they’re so easy to service,” he reasoned.

Seamus dissolved into fits of derisory laughter. “Easy to service??” he practically shrieked, “I can picture it now! A terrorist cell emerges from the shadows, swoops down on the Ford Cortina! Lifts the bonnet! Checks the filters! Checks the points! Changes the spark plugs! Fills it full of Semtex! And then blows it up!”

His dad dismissed this. Seamus obviously just didn’t know about cars.

Nonetheless, the horror was there. Seamus took me with him to talk to his auntie who lived in the Unionist Protestant neighbourhood of Chief Street. A Peace Wall had been erected across it. The wall was an impressive brick and concrete barrier topped with barbed wire which closed off Chief Street and separated it from the Catholic Nationalist neighbourhood of Ardoyne. Every house between the Peace Wall and Seamus’s auntie’s had been burned out.

Chief Street was a stronghold of the Protestant paramilitary UVF and Seamus told me I must under any no circumstances call him anything but Lawrence. I was so terrified of blowing the gaffe, I hardly said a word while we were there. Seamus’s auntie must have thought I was simple.

Nevertheless, she was incredibly hospitable, as almost everyone I met there was; and she made tea and served it with biscuits (cookies) on delicate china with doilies on the tray and a lace tea cosy on the pot. She talked about the terrible times of the past few years; how she had always had Catholic neighbours, many of them friends, all the way down the street; and it had never been a problem. With the onset of the Troubles, and sectarian riots, her Catholic neighbours has fled Chief Street and her Protestant ones had fled the Ardoyne. She didn’t know how it was all going to end. Half the street, she told me, were “taking tablets for their nerves".

While we were talking I glanced out the lace curtained window. Three men drove up in a battered white van and stopped in front of a burned out and boarded up house. They took a ladder out of the back, looking for all the world like builders about to start a job. They put the ladder up against the wall to get access to the upper floor window. One of the men climbed up and went inside through the window. Another man stood at the bottom. A third man went to the back of the van and started to unload arms and ammunition, handing them to the man at the bottom of the ladder, who ferried them up to the window, where they were taken inside. Having discharged their load, the ladder was put away and the van drove off again.

The conversation over the china tea cups with custard cream biscuits had continued throughout as if nothing out of the ordinary was happening which – for Seamus’s auntie at least – was probably true.

On our way back to the car Seamus said to me quietly, “There are a lot of people who would cheerfully kill you to know what you know right now. Never mention it to anyone. Not anyone.” I didn’t.

Meanwhile, I had been busy typing up reports and press releases for NICRA, who were engaged in campaigns against Internment without Trial, the issue at the heart of the protest on Bloody Sunday six months before, when fourteen unarmed civilians were killed by the British Army; against the Widgery Report which exonerated the soldiers that had done it; and against the ongoing casual discrimination against Catholics that had given rise to the Civil Rights Movement in the first place.

I was typing up some statistics when I discovered that Catholics suffered 25% unemployment as against nearly 12% for Protestants. And that 19% of Catholics were living in sub-standard housing compared to about 10% of Protestants. And the penny dropped for me.

If my community was suffering 12% unemployment, and if 10% of them were in substandard housing, I would be terrified of any group whose demands for parity seemed to threaten that already meagre piece of the pie. Surely it would be better to fight for a bigger pie? But the bakers were off sprinkling salmonella into the metaphorical eggs. And one of the bakers was Ian Paisley.

Ian Paisley fascinated Seamus and he was keen to analyse the political content of some of the Reverend’s sermons as part of his research. The only problem was that he would need to go to the church and record them, and he had no idea how the hell he was going to smuggle a cassette recorder in to do it. But necessity is, I guess, the mother of invention and Seamus’s audacity and courage in the cause of academic research knew no bounds. So he got me to do it.

Now, when you are eighteen years old, which I was then, you have no sense of danger; you really just don’t believe anything too bad is going to happen to you. So I was happy to agree to it. It seemed like an exciting thing to do in fact. The plan was for me to go to the church with Seamus with the cassette recorder concealed in my handbag. So Seamus’s mother, always keen to support her lad in whatever daft thing he thought of doing, cheerfully went to fetch a few of her handbags to find out which one would be most appropriate for this purpose.

I had never been in a Protestant church in my life. It used to be a mortal sin for a Catholic to attend a Protestant service and, being a good Catholic who wanted to stay out of hell, I had always obliged God on this issue. (Now that it’s not a mortal sin, what happened to all the people who attended a Protestant service and died before going to Confession?) Seamus told me I would be alright as long as I said absolutely nothing and did exactly what he did.

His minister father was known to the elders of the church, so our arrival aroused no suspicion. We were greeted at the door by someone who knew Seamus, and who shook his hand warmly, asking how he was getting on with his studies out in California. It was going well.

They exchanged a bit of chit-chat. Seamus introduced me as his American cousin (I smiled, shook his hand, said nothing). We were handed the Order of Service or somesuch bit of paper. And we proceeded into the church. I followed him down the aisle until he came to a pew close enough to record from, but not so busy we could be too keenly observed. As he turned to go into the pew a strange and almost irresistible compulsion came over me that I was only able to fight back in the last split second.

I came and sat next to him. He bowed his head and covered his face with his hand as if in prayer. I did the same.

“Jesus Christ!” I whispered. “I nearly genuflected!” Seamus covered his face with both hands.

The Big Man came on. The service began. I have to say I got into it after a while, and quite enjoyed the intense ritual of Protestant praying. But then the Reverend Paisley got each and every one of us to bow our heads and pray very, very hard to discover which of us God was going to save today. We all had to keep our heads bowed and our eyes squeezed shut while he waited for someone to be moved to stand up and ask to be saved. The wait went on and on. And I realised to my horror, that we were not going to be allowed to leave the church that day until someone owned up and asked to be saved.

After a very long time, I sneaked a peek to see if anyone had cracked yet. But the congregation was a sea of bowed heads. Ian Paisley’s continued exhortations for someone to ask to be saved began to have a hypnotic effect on me. Someone needed to do it. Someone needed to be saved. All I had to do was stand. All I had to do was stand…

Seamus had his eyes open too and was staring at me, a strange kind of terror in his eyes. “Don’t. You. Dare.”

So I didn’t. But someone else did, and we were finally allowed to go home.

I had recorded the Reverend Paisley’s sermon without a hitch, but it turned out to be pretty boring in the end. The only controversial bits were a few barbed jibes aimed at the Pope. Big deal. Had I really risk being hung, drawn and quartered as a heretic for that?

One day this demagogue, who had held us all hostage that day, would be First Minister of the Northern Ireland Assembly. Other demagogues and hostage-takers would sit down with him in an uneasy peace. But before that would happen, decades of blood would be spilt.

Seamus never asked me to go back with him to Ian Paisley’s church. I don't think he wanted to risk me reaching for the holy water fountain next time. And I probably would have.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on "Post a Comment" below.

1 comment:

Dam Donna, You never quite managed to get around to telling that little gem of a story.

-Tim :)

Post a Comment