Juanita Gonzales was shorter than I was, which was pretty damn short. I don’t think she could have been more than four foot ten. She was the pastry chef at the ASUCLA (Associated Students of the University of California, Los Angeles) cafeteria; and I hope I am not being disrespectful when I say she certainly looked like she’d sampled a few of her own pastries over the years.

I’d started work on the steam table there in my second year at the university; doling out ladles full of chilli and soup into cups and bowls, and pouring copious amounts of a brown glop called gravy, not just onto mashed potatoes, but onto all the meat and vegetables that were passed to me on plates by my steam-table partner Carol. This was an attempt to disguise the fact that the meat was dry and the vegetables soggy. It failed.

Carol was a spinster of about thirty-five, whose top half always seemed to be walking faster than her legs. She had an intense expression most of the time and explained to me the finer points of chilli, explaining that a cup held one ladle of chilli, and that the bowl (which cost quite a bit more) held exactly…one ladle-full as well. She had never questioned this and was meticulous to the letter in carrying out her duties. It was what she got up in the morning for.

I worked there twenty hours a week while taking a full load of classes. It was a friendly group. There was the irrepressibly cheery Teresa, who brought baked goods of all kinds in to share with us, the popular and handsome fast food chef Raul, the scatty dyed-blonde Paula, the laconic and almost severe Dolores, Big Red the dishwasher, Barut from Lithuania and Edna who would always take her shoes off in the break room, oblivious to the odour, and secretly complain to me (as one white person to another) that the Mexicans weren’t as meticulous about hygiene as “we” were. As is often the case, though, her racism didn’t stop her from backing up her fellow Latino workers when they were harassed, and offering her shoulder to anyone going through a hard time.

I hadn’t worked there long when I discovered that ASUCLA Food Service used non-union lettuce. It might seem a small thing now, but this was the early 1970s and Caesar Chavez’s United Farmworkers Union had been fighting to defend impoverished agricultural workers in the vineyards and lettuce fields of California for years; and it had become a cause celebre of the time. The farmworkers had voted to be represented by the UFW, and the growers had responded by doing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters Union, who sent an army of big, surly goons to protect the growers from the small band of protesting workers who picketed outside their gates. Those picket signs can be dangerous weapons, I guess. Only the smaller growers signed contracts with the UFW, and, in those highly charged political times, it was a point of principle to boycott non-UFW produce. Which was how I began my letter-writing campaign to the Daily Bruin.

The Daily Bruin was the UCLA student newspaper and just about everybody on campus read it – mainly because it was free. I wrote passionate letters, not only about the scandal of the non-union lettuce, but also about the fact that the male food service workers had their uniforms laundered for them by ASUCLA, but the women had to wash their own (being natural domestics!); and I even blew the whistle about the Great Chilli Rip-Off. The whole student body was shocked by my revelations, then outraged, and finally demanded action – about the chilli at least. Management had to order in new bowls to placate angry diners.

We did eventually get action on the uniforms (the president of the Student Union was a woman that year and unimpressed). And after a short campaign, the cafeteria was forced to switch to union lettuce, which was greeted with jubilation by the largely Hispanic workforce. When the kitchen workers opened the very first box of union lettuce, they tore off the cardboard panel with the UFW logo on it, and hung it victoriously on the kitchen wall.

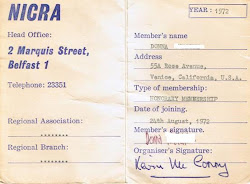

My letter writing campaign had not gone unnoticed by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Workers (AFSCME) Local 2070. They had been trying to get a foothold at ASUCLA Food Services for a number of years, so they sent an organiser out to talk to me. He bought me a cup of coffee and by the time it was finished, I’d agreed to help unionise the cafeteria. It took over my life for the next three years. I should have asked him to buy me lunch as well.

One thing I have discovered about the injustices of the world is that the reason most people don’t do anything to right them is not because they don’t notice or don’t care, it’s because nobody thinks anything can change. The ASUCLA workers knew that the wages they were on put them below the poverty line; and that it was unfair that the semi-skilled workers were on minimum wage; and that workers seemed to be fired, laid off, moved or have hours cut without explanation. They knew that there were safety issues that needed to be addressed: like uncovered drains that we regularly tripped on and refrigerator fans that didn’t have guards on them that were certain to result in lost fingers sooner or later. When people start to believe, however, that something can be done, things can change fast.

Juanita Gonzales was one of the first to join the union. Teresa filled out her card the next day. Dolores joined. And Carol. And even Edna. Some refused: like Paula who said she didn’t need a union (even though she would be fired while on sick leave less than a year later), and Barut who said she didn’t believe in them and thought that, though she found it almost impossible as a single mother to keep her kids in shoes, it was not her place to challenge the management’s God-given right to do whatever they wanted. Nevertheless, management were about to have that God-given right challenged.

The first time they had to take notice of us was when Dolores was called in for a disciplinary meeting by Sandy Hammer, the Head of Personnel. Dolores had been moved to the breakfast shift and started to be late because the first bus of the day to get her to work couldn’t quite get her there in time. I had just been elected shop steward and Dolores exercised her right to have a union representative present. I had never met Sandy Hammer before, but within a very short time she was going to wish she’d never set eyes on me.

Dolores was taken off the breakfast shift, and word started to get around that the union was worth joining – and many more did. Management were not at all happy with the direction this was going and started to do whatever they could to turn the tide. They moved me to the fast food bar to get me out of the cafeteria. They tried (and failed) to cut my hours down to eight. They even confronted me with an accusation that I was threatening to pour scalding hot soup on anyone who didn’t sign up. (I was appalled by this libel, but I had an airtight defence. ASUCLA soup was never hot enough to scald anyone.) But by then the organising drive was so much more than one person; and we even had another shop steward: Juanita Gonzales.

Juanita turned out to be a fantastic shop steward. She was sharp, clear-headed and spoke Spanish, the language of the majority of the workers. She inspired trust and hope; and she put paid to any idea management had that the union organising drive would end with my graduation.

Several months later, Juanita needed major operation. She had been working for ASUCLA for ten years at that point and she asked for ten weeks (unpaid) sick leave to travel to Mexico for the surgery and then to recuperate with her family in her tiny hometown in the remote south of the country. She was told the management would give her six weeks, but that there would be no problem if she needed more. She only needed to write to let them know what was going on. So off she went with our best wishes for a quick recovery.

Ten weeks later I was delighted to see her back, dressed in her uniform and sitting in the break room. In a moment, though, I sensed something was very wrong.

“I have no job,” she told me. She had turned up for work only to be told to go home. She handed me a letter they had sent her while she was in Mexico. She couldn’t read English and she didn’t know what was in it.

When Juanita was not well enough to return to work after six weeks, she had written to her Hispanic boss to say she couldn’t come back for another four weeks. Her letter was in Spanish, and she apologised for this, explaining that she was staying in a small, remote place where there was no one to translate for her. The letter she received in reply was in English and she had assumed it was simply acknowledging her letter. She didn’t know that it said she was fired.

I immediately filed a grievance for unfair termination and they immediately refused to consider it. A termination, they explained, had to be grieved within four weeks. It did seem that responding to her letter in English, knowing that she wouldn’t be able to know what was in it, had been a stroke of genius on their part; one less shop steward.

It was something we had to fight and we did. The union demanded a meeting with us and a member of the ASUCLA Board of Control for Sandy Hammer to explain why Juanita Gonzales’s job could not have been kept open for another four weeks. It was, Ms Hammer explained, because there were simply no jobs that she would have been able to come back to. I countered that the Food Service had been advertising in the Daily Bruin in the same week they had fired Juanita. She insisted the only jobs that had been advertised at that time were hot dog sellers for the UCLA football games, which obviously weren’t appropriate. The Board of Control member was satisfied; I wasn’t.

The next day I went to the Daily Bruin office and I bought back issues for the week Juanita was fired. When I discovered that they had been advertising for at least four ordinary full-time jobs in the cafeteria, just as I’d claimed, the red mist descended. I stormed up to Sandy Hammer’s office, the paper in my hands, rushed past the secretary (who, just like in the films, said something like, “You can’t go in there!”) and interrupted a meeting she was having.

“There!” I said throwing the paper down and stabbing my finger at the ad, “Right there! Full-time cafeteria workers!Sometimes I think you lie by reflex action!” I spat (which I thought was a pretty good line considering I hadn’t had any time to prepare it), before storming out as suddenly as I’d come in.

This accomplished nothing, of course, and it was obvious that if we were to save Juanita’s job and the accrued benefits (including medical!) of her ten years employment, something drastic was going to have to be done. So we decided to occupy a meeting of the ASUCLA Board of Control.

Leaflets went out to the employees of the Food Service and to the university students. We were to gather for a short rally after work and then march to the Student Union building where we would burst into the meeting and refuse to leave until Juanita got her job back. It did occur to me that, as the “ringleader”, I was going to spend that night in jail. Now I am not a courageous person. I run away from bees, for God’s sake! And I remember working that day and repeatedly having to excuse myself to go to the restroom. For the first time I knew that the expression “scared shitless” can actually be literal.

When Juanita and I and several of our co-workers arrived at the rally, I was stunned to see that there were almost a hundred people there. The union organiser spoke to the crowd. Then Juanita spoke. And then I spoke. It was the first time I had ever done anything like that and apparently I spoke well. I have no memory of it. It was November 20th, 1973; two days short of my twentieth birthday.

After our short rally, the group headed off for the short march to the Student Union building where the Board of Control meeting was taking place. I was terrified. My thoughts were racing. What the hell am I doing here? And it did occur to me, with my hand on the doorknob, about to go in, that I might look behind me and discover no one was there with me. What would I do? Pretend I had been looking for the restroom and opened the wrong door? I opened the door. The Board of Control were sitting at a long table and looked up, startled, as I entered. The room filled up behind me.

“We’ve come here to talk about Juanita Gonzales,” I said.

I didn’t get arrested, the occupation was a success,Juanita Gonzales’s case was referred to Arbitration and she was put back on full pay pending the outcome. We had won our first battle, but there was still a war to win.

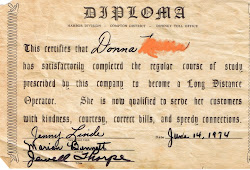

Arbitration is a formal procedure, like a court hearing, and the union employed a canny and passionate young labour lawyer called Hirsch Adell.

At the very beginning of the arbitration hearing, the lawyers from both sides exchanged their copies of the same key documents in order to agree that they were “Joint Exhibits” (i.e. papers they were both going to use in presenting their cases). Among the papers exchanged was a copy of the translation of Juanita’s letter in which she asked for her sick leave to be extended. Our copy of the paper was handed over to their lawyer, who then handed it on to the arbitrator. This left their copy of the letter in our hands. During a short recess, Hirsch came over to us, holding the paper.

“We’ve just won this,” he said. It took half the afternoon for us to see how he knew this.

Management’s case rested on their sincere attempt to keep Juanita in her job, as evidenced by a meeting they said they had on August the 3rd 1973. At that meeting various proposals were made about how they could keep Juanita on, but, sadly, it just could not be made to work and they had been forced to terminate her employment.

I watched as Sandy Hammer was cross-examined by Hirsch Adell after she had given her sworn testimony. He asked who had been at this meeting? She replied that no fewer than two other managers were there (since they were taking the matter so seriously!). He asked how long it had lasted, what options had been discussed and how the decision had been reached. And he also asked about Paula.

I had forgotten about Paula. She hadn’t asked for union help when she was fired under very similar circumstances while on sick leave a few months before. When pressed, Sandy Hammer “couldn’t recall” if a similar high-level meeting had been called to preserve Paula’s job.

And it was at this point that he handed her the copy of the translation of Juanita’s letter that had been in their side’s hands only that morning. There was, Hirsch pointed out, a note written in the margin. He asked whose handwriting it was. I saw Sandy Hammer’s face go white.

“It’s mine,” she said.

“And can you read it for the record?” he asked.

“It says, ‘Send her the letter we sent Paula.’”

Hirsch moved in for the coup de grace. “And what date is on your note?” She must have known it was all over then.

“The 21st of July, 1973.”

“So,” he said, reeling in the fish he knew he’d hooked that morning, “You were instructing the manager to send the standard termination letter, the ‘letter we sent Paula’, to Juanita Gonzales two weeks before you had the meeting to try and save her job?”

Their case collapsed. And, irked by their apparent lying under oath, the arbitrator ruled completely in our favour, compelling ASUCLA to permanently reinstate Juanita Gonzales with full back pay and full benefits. We had won!

There was a real sense of euphoria when she returned to work, and returned to her duties as shop steward for AFSCME Local 2070. But it didn’t last.

Very conveniently, a few weeks later there was an immigration raid at the cafeteria and INS officers arrested and deported about two dozen of our workers. Though most of them were back within a week, the workforce was reminded just how precarious their livelihood could be; and euphoria had turned to uncertainty.

A few months later Juanita collapsed at work. She was hospitalised and eventually diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis; and she was never able to return to the job she (and we) had fought so hard to keep.

I went to see her when she was recuperating at home in West L.A. It was a three bedroom stucco house, not unlike the one I grew up in; except that maybe twelve or fifteen members of her family were living there, including children in hand-me-downs and wearing zorries (flip-flops); the shoe of choice for parents who can’t afford shoes. Two or three of her family were in work and just about earned enough to pay the rent. The living room had sheets hung up dividing it into three separate spaces. Behind one of those sheets was Juanita’s “bedroom”.

Her condition had deteriorated a lot since I’d last seen her. The cruelty of this twist of fate, after such a long struggle, tasted bitter in my mouth. But not in hers. She said that, if it hadn’t been for the union, she wouldn’t have the medical benefits she now needed so desperately. Which was a point, I guess.

She said she wanted to give me a present. To thank me for everything I’d done. And she handed me a brown plastic folio with a zipper at the top.

“To keep your papers in,” she said, “You have many papers!”

Raul replaced Juanita as the main steward at ASUCLA Food Service. He was dedicated and passionate, but fear had begun to replace hope among the workforce. And as I drove away that day with the brown plastic folio that would become one of my most treasured possessions, I wept.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

1 comment:

Now I know where the passion for The Key came from...keep writing please!

Post a Comment