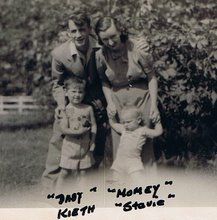

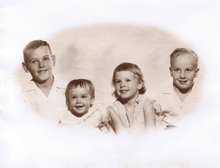

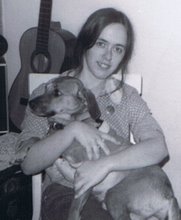

When my mother brought me home from the hospital, a tiny, squalling bald blob, and laid me out on the yellow chenille bedspread for everyone to see, my brother Steve said, "What do we want her for?" Relations between my brother and I went downhill from there.

He teased me mercilessly throughout my childhood and nothing pleased him more than the impotent rage he could inspire in me without having to work at it very hard. My mother and grandmother, when they furnished our house, bought a coffee and end table set with the latest "no mar" finish so that, under the onslaught of four small children, the tables might still remain pristine. This lasted until I chased Steve with a scissors in my hand and, because he could outrun me, ended up throwing it at him with all my pathetic might. It missed him and bounced onto the "no mar" coffee table, taking a small gouge out of it. My mother was furious and I said I was sorry, but mostly I was sorry the gouge hadn't come out of my brother instead.

My mother never changed her furniture throughout her life and that gouge remained, forever reminding me of the troubled relations between my brother and me.

Nevertheless, I looked up to my brothers and desperately wanted them to accept me and include me in all the terribly interesting and exciting things they used to do. They only included me, however, when I was of some marginal use to them. I knew this, but didn't mind. Better that kind of attention than none!

So when they played "pickle" they let me be the runner. They each stood on a homemade "base" (usually a bare patch of lawn) in the backyard and threw a baseball to each other. I was supposed to run between the two bases at random intervals and they had to try and catch me out. After a while this became pretty dull and I whined and pleaded for them to let me throw the ball for a bit, while one of them tried to steal bases instead. Fearing I would strut off in a huff and they would lose their runner, they decided to let me do it for five minutes. On my very first throw I hit my brother Keith with the baseball and he came crashing to the ground, writhing and groaning in pain. I couldn't believe he was being such a baby over a little thing like a ball hitting him between the legs! They never let me throw the ball again.

The only time I can remember my brother Steve treating me with real concern and affection was once when I was about nine and he was practising his archery. I watched admiringly for ages as he shot bulls eye after bulls eye, until Steve finally decided to let me join in.

"Here," he said, taking the target off the washing pole where it had been hanging and handing it to me, "You hold that up and I'll shoot at it."

I was so delighted. My big brother was letting me do archery with him. I stood about fifteen feet in front of him and held up the target. It was just like William Tell without the apple. As he prepared his shot and brought back the bow, his hand slipped (or so he said) and the arrow flew wildly off the string. The next thing I saw was something dangling from my head; the arrow had hit my head at the hairline and gone under my scalp. When I realised what it was I started to cry. My brother rushed to me, pulled the arrow out, looked at me with great brotherly tenderness and said, "Don't tell Mom!" He took me to the sink and cleaned the cut on my scalp and told me that this would be our secret. After nine years my brother Steve and I had bonded.

Steve was asthmatic and dyslexic and struggled at school, where the nuns branded him stupid. He was badly bullied by the other boys, arriving home more than once with blood down the front of his white shirt. Of course back then nobody thought bullying was a problem; in fact they tended to think it was character forming. If that was true, Steve must have had the best formed character in Bellflower.

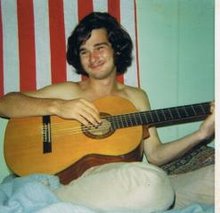

But when he hit his teens, he became a Wild Child.

The first inkling that my brother was going to be a "problem" was when I came home at dinnertime and there was no dinner on the table. My mother was in a terrible state and had to go out, she said. Steve, at the age of fourteen, two years before he had a driver's licence, had secretly taken the Galaxy station wagon Mom had bought to replace the now deceased Plymouth, and gone joy-riding with his friends until he was stopped by the police. He wasn't charged with anything, but Steve's teenage rebellion was only just beginning.

My mother had placed both my brothers in a boys Catholic school run by Salesian priests and brothers, in the hope that the male culture of the school would be good for her fatherless sons. My brother Keith was a quiet and studious boy, a bit of a geek really, and caused no trouble. Steve, who hated the school and everything about it, was determined to find a way out.

My brother was an atheist at an early age and he saw the opportunity to get his wish during a routine religion class - a usefless subject, he thought, of no value in the school curriculum - run by a priest who had little tolerance for bad behaviour. Steve had put his head down on his desk for a little nap during the lesson, which he must have known would be an act of extreme provocation.

"Hey!" the priest demanded, "What are you doing?"

"I'm sleeping," my brother answered.

"Why are you sleeping in my class?" he asked, rising to my brother's insolence.

"Cause I don't consider this a class," Steve replied defiantly.

"Well, maybe we don't consider you a student!"

My brother shrugged and the priest ordered him to leave the class. Steve picked up his books and loped to the door, unconcerned. The priest finally lost it, wheeled my brother round and slapped him hard.

It was an instinctive reaction to slap him back (or was it?) and the priest exploded, punching Steve in the face – whereupon Steve punched him back. The boys in the class were out of their seats in an instant, the desks were pushed back, and there at the front of the class the priest and my brother fought it out until a couple of teachers arrived on the scene to pull the two apart.

My mother was, naturally, called to the school and Steve was now sure that, in the wake of this incident, he had a ticket out. The principal, however, decided that Steve was disturbed rather than "bad", and the best thing for him would be to remain at the school where he would benefit from the discipline and pastoral care that would be on offer.

The discipline and pastoral care didn't take, though, and my brother seemed more and more like a runaway train headed at great speed to the edge of a cliff. His friends included hippies and bikers and petty criminals; and there was a lot of drugs in there too. My grandmother had always believed in him, insisting he had a heart of gold (he did) and my mother prayed that somehow he would come out of all this alright. But it didn't look good.

One morning at breakfast my mother was in a foul mood. She banged the dishes on the table, slammed cupboards and kicked the dog out of her way. None of us dare ask what was wrong. It took a long time before she spoke.

"Well, you'll be pleased to hear your brother's in jail!" I didn't know why she thought we'd be pleased. I had yet to discover irony.

My brother had gone out, crashed the car into a bridge and been arrested for being Drunk and Disorderly.

Eventually Steve was diagnosed with borderline schizophrenia and ended up in the psychiatric ward of the local hospital. It was something we were not allowed to talk about outside the family due the stigma and shame it would bring upon our house. “If you tell anyone,” my mother warned, “they’ll think we’re all crazy.” Of course we all were. Absolutely barking in fact.

My brother spent a fairly unproductive summer in the hospital, and was put on a lot of drugs that looked like their ultimate purpose was to turn him into a zombie. He became adept at not taking them and eventually, because he got intensely bored, plotted and carried out a number of daring escapes from the ward. He would then hitch-hike back to our house, have a quiet lunch with my grandmother and then hitch-hike back to the hospital. When he knocked at the front door, it didn’t half piss them off. Like I said, though: My brother was a genius.

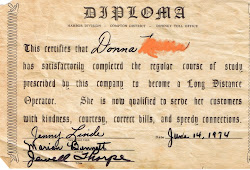

It was a long time, and a very hard road, before my brother's genius was finally recognised. He got in at the beginning of the computer hardware boom, got a job drafting the circuitry of silicone chips (which, at that point I had never heard of before), worked for people who weren't as smart as he was but who had gone to college, eventually lied about having a degree, advanced quickly to the top of his profession, designing hardware for cutting edge systems and sharing in the patent of a number of inventions.

Ironically, Steve, despite his eccentricities (of which there are many!), turned out the sanest of all of us. He has been happily married over thirty years.

Many years ago I was sharing a bottle of wine with his wife and, as women do sometimes, we were swapping stories of how and when we'd lost our virginity. She had met this deadbeat when she was a teenager and decided that, as all her friends had lost theirs, it was time she got rid of her virginity. (This was the Sixties, you know.) The next morning, the guy was up, out of bed, pacing and trying to explain the situation to her.

"Last night was good, but you have to understand you can't hold me. I am a free spirit. I am like the wind. Trying to hold me is like trying to catch a moonbeam." (Okay so he probably wasn't anywhere near as poetic as that, but you get the idea.) She thought this guy was really a jerk.

"And do you know who that guy was?" she asked me, "Your brother."

No comments:

Post a Comment