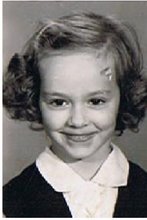

It was 1959 when I started school and single mothers hadn’t been invented yet. At least not at Catholic schools where parents were expected to stay together no matter how miserable they were, and mothers wore sunglasses to pick up their kids whenever they had a black eye or two. Fortunately, it was a sunny climate.

There was only one other kid in my entire school that didn’t have a dad and that was Peggy Wilson whose day was dead, which was at least respectable. And when, in religion class, Sister Wilma talked of the importance of Jesus’ diktat that “what God has joined together, let no man put asunder” (which I thought would be a good reason to have all-woman divorce courts), she added that the children of broken marriages are “just a little less favoured in the eyes of God.” She didn’t look at me. She didn’t have to.

All my friends had dads, who sat in front of the TV watching football and drinking beer, or built stuff, or fixed broken stuff in the house. Susan Tratz had the coolest dad of all because he had a metal messkit from the Battle of the Bulge, which he showed off with great pride because he’d been a medic and, when supplies weren’t getting through, had to take a bullet out of a man’s guts with the messkit knife. He never said whether the hapless soldier survived, however.

Although I didn’t have a dad, I did have two parents; my mom and my grandma. My grandma had had a hard life. Her father had died when she was very young, and her sister had been stricken with polio. This, I was told, was the reason Great Aunt Irene used to talk to herself constantly and resent it if you tried to enter the conversation. I have never read that polio can be responsible for that kind of behaviour, and I was pretty convinced she was hearing voices that weren’t there. When their mother had to quit work because “she became confused”, (the family mental health picture has never looked particularly rosy), my grandmother had to go to work to support them all. She was just fifteen years old.

She accepted this with great stoicism and, despite the fact that she’d never been able to get an education, was one of the most well read and well informed people I’ve ever met, with the possible exception of my mother. Unless you had really done your homework, it was a bad idea to try and argue with either of them, or my Aunt Lucille either who once invited a Jehovah’s Witness into her living room, and debated with her so fiercely, the poor woman fled!

Grandma bore the lifelong responsibility of caring for her “confused” mother and my Great Aunt Irene. She was married late and widowed young; and was sustained by the intensity of her Catholic Faith.

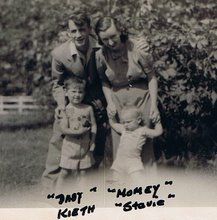

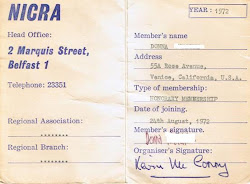

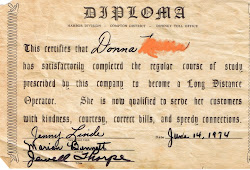

When my mother’s marriage collapsed, my grandma took us all in and my mom went to work in the Ovaltine factory, earning half of what a man would doing the same job. Grandma assumed, without question, the job of looking after us kids until my mom got on her feet. She stayed for the next thirteen years.

She must have been only fifty-nine when we first lived with her, just six years older than I am now, so I it’s funny to think how painfully old I always thought she was. She was very short, walked with a slight limp and her white hair, which she always wore under a hairnet, was so thin that it seemed only a dusting of snow on the expanse of her scalp.

Having survived poverty, the Great Depression, and the privations of World War Two (when God spared her son by ensuring the war ended before he could be shipped out), she was tough as old boots. I never heard her complain about anything and only saw her cry twice in my life. She was utterly unsentimental about everything except, secretly, children.

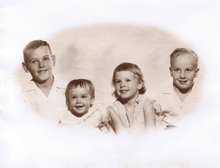

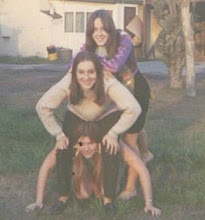

She loved us with the passion of Mama Tiger! Keith was special because he’d had a hard time during the divorce. Steve was special because he’d had club feet and was asthmatic. Nancy was special because she had such a good heart. And I was special because…well, because I was hers.

I was the only one to have been raised from a baby by my grandma, and I was the last one left at home when my brothers and sister went to school. It was probably the only time I ever had an adult’s undivided attention as a child. And I gloried in it!

She taught me all the things girls were supposed to know back then; how to do the washing (using bluing for the whites. When did they stop using bluing anyway?), make up the beds, clean, sew, mend, cook and bake. On sunny summer days we went out into the yard to hang the washing out and I handed her the clothes pins. On rainy days we stayed in to make fudge; a recipe I still have burned into my memory and involving such eccentric measurements as: three “bent spoonfuls” of corn syrup. The bent spoon from the drawer was the only trusted measure for her recipe.

When I was teased mercilessly at school, she would feed me stories of how they were all jealous because of how smart I was (which made me wish I was stupid!); and when I pretended to be sick so I wouldn’t have to go to school to face them, she would say, “You’re sick of school I think,” wink and let me stay in bed. When I started to write my stories, she would listen while I read them out to her as she ironed. Now I’ve raised a kid myself and I realise this must have been a good way to keep me occupied while she was ironing, but this was beyond the call! I wrote screeds of the most childish drivel, that went on and on and on and on! (Like my blog stories, in fact. So you see what I mean.) But, not only did she listen patiently, one day she said, “When you grow up, you’re going to be a writer.”

“I can’t be a writer,” I said, “Girls grow up to be housewives.”

“Who says?” she demanded, “Is your mother a housewife?”

I looked away. That my mother was not a housewife was surely a source of shame, not pride.

“Girls can be anything they want to be!” she insisted, “And you should be a writer.”

My grandmother hated anything she thought was unjust. She had hated Herbert Hoover during the Depression for declaring, “If you don’t work, you don’t eat,” as thousands starved and the Midwest turned into a Dust Bowl. She remembered the signs in the ads as she struggled to find work that said, “No Irish Need Apply” and felt a visceral connection to the Civil Rights Movement and their fight to confront that kind of prejudice. She once admonished me for saying, at the age of nine, “Black and white are equal, white skin is prettier than black skin.”

“No it’s not!” she snapped, “You think that only because you’re white, and that is prejudice! Black skin and white skin are both as beautiful in the eyes of God!” (My grandma brought God into an awful lot of stuff.)

Most of all she hated that women were such second class citizens,, and that my mother was being paid half of what she was worth because of her gender, which, at the end of the day, meant that we wore hand-me-downs and patched jeans, and ate hash and pot roast, and had lean Christmases.

Grandma believed passionately that God had put us on Earth with a mission to leave it a better place than the one we arrived in, no matter how small that effort might seem. We lived across from the school and, when the street inevitably flooded in heavy rain, she would wait on our porch with dry towels so that, when the kids waded across in their bare feet, they could dry them off before putting their shoes and socks back on and walking home.

My mother regularly worked twelve hour days, six days a week; and when she wasn’t working she was often crying. Depression hadn’t been invented yet either, except among rich people. But I knew she spent an awful lot of time on the edge and I was sure that, if my grandma ever left, we would all be cast adrift and battered to death on the Rocks of Life.

If I came home from school and couldn’t find Grandma, instead of looking in the yard (which was where she invariably was), I would check to see if she’d taken her clothes. I would have nightmares and wake up crying and when she came asked why I’d say, “Cause I’m scared you’re going to die someday!”

“Of course I’m going to die someday!” she’d scold, “We’re all going to die someday! Now go back to sleep!”

When she was diagnosed with cancer, I was eleven years old. My nightmare fears were finally invading my life as I knew they would one day. So I did a deal with God. I was too young for my grandma to leave me, I told him. And I asked Him if He would just leave her with us till I was sixteen and able to deal with it. God fulfilled his part of the bargain. Grandma went into remission and stayed well for another five years.

One day my sister and I came home from school and Grandma was lying on the couch unconscious and twitching and Irene was flapping about not knowing what to do. I knew she must be really upset because she was talking to us.

We called an ambulance and they came and took her away to the hospital, reassuring us that everything would be okay. I remember thinking, “How the hell do you know?”

She’d had a stroke and no one thought she’d last the night. I visited her with my Mom and my Aunt Lucille and my sister when she regained consciousness. Her speech was very slurred and she couldn’t use her left side. She took my hand and squeezed it, trying to say something to me.

“What are you trying to say Mom?” my mother asked.

My grandma said it again. And again, becoming more frustrated.

“Sorry, Mom,” my Aunt Lucille laughed, “I think we’re too stupid to understand!”

But I knew what Grandma was saying. I could decipher it. Why didn’t I say? Why was I embarrassed? She was saying, “I love you.” I should have said I love you back. But I wasn’t used to her being sentimental.

Grandma miraculously recovered from her stroke and was ready to be discharged from the hospital when the doctors discovered that her cancer had come back. And that she was dying.

It was a pretty cruel trick on God’s part, I thought; and he had obviously exploited the fine print in our contract. My grandma died a few months later, just after St. Patrick’s Day, when I was sixteen years old. I was left wishing I’d done a better deal with God.

She died as she’d lived; poor. Her worldly goods consisted of little more than a few knick knacks, religious items and a closet full of old and faded dresses, bar the one she wore at Sunday Mass.

I’m sorry she never lived to see me become a writer, but, in any case, I was a late bloomer and she would have to have lived to be 101. But she would like to have been right. She did like being right.

Her legacy to me was a recipe for fudge, her bent spoon, a wicker laundry basket complete with clothes pegs, the skills of bed-making, sewing and making do, the secret of good parenting, which is unconditional love, a hatred of injustice, and her conviction that Jesus really did mean it literally when He said:

“I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me. Truly I say to you, as you did it for one of the least of these my brethren, you did it for me."

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

3 comments:

I cannot describe how much I love reading your blog Donna. I love your grandma!!! What an amazing woman! I see you inherited a lot from her. YAY.. go grandma and go Donna!!

love you!

Justy

xoxox

louie says..

i ditto what les is saying here. your grandma sounds like a really women, and grandma to have. i was nearly in tears reading.

and i think your writing is great because theres so much too it.

((((((((hugs)))))))))

xoxox

your blog has a great title and very heartfelt and genuine topics, well done. If you enjoy a good read feel free to check out my blog www.davincisbloglog.blogspot.com

10 December 2007 17:32

Post a Comment