On my tenth birthday I had planned to have my first teenage-style birthday party, playing the latest 45s (including Donna the Prima Donna which had just come out!) and trying out The Twist with my friends. But that morning, President Kennedy was shot in Dallas. Which kind of ruined the party.

I was devastated. I had idolised him like my friends idolised pop stars. I had an album of his Greatest Hits (speeches), and had started a John F. Kennedy Fan Club among my semi-reluctant friends. I had even written a Club Song called PT-109 about his heroism in WWII. So I had decided that I wanted to go to Harvard University just like him. My grandmother tactfully explained that Harvard was a male-only university, which I thought was the stupidest thing I’d ever heard! How was this possible? But then I found out that it had a sister university for females called Radcliffe, which I grudgingly thought might do, so I told my mother that I wanted to go there.

“Yeah?” she drawled, “And who’s going to pay for it?” The idea that financial considerations could limit one’s horizons had not occurred to me yet. But I still felt sorely aggrieved.

When the time came I applied to UCLA, which, as a California resident, was a much cheaper option. It had the big leafy campus with very old buildings that was a minimum requirement for me. And it had a certain cachet. In 1969 the Communist UCLA professor Angela Davis had become a cause celebre when she was first fired and then arrested on trumped up charges which sparked the “Free Angela Davis” campaign that led to her acquittal. That sounded cool enough for me.

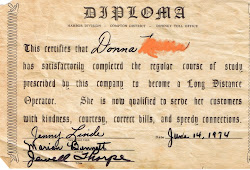

I was nominated, along with five other kids, for the North Downey Women’s Club Scholarship. North Downey was one of the most salubrious neighbourhoods in the area (some of the houses even had swimming pools, and Karen Carpenter lived there). So, when confronted with the prospect of attending the North Downey Women’s Club Awards Luncheon, I had had to spend six whole dollars at the Goodwill Shop to find something appropriate to wear.

When the day came I have to admit I was pretty intimidated. There did seem to be an awful lot of women getting out of expensive cars. Well, they were new anyway so they must have been expensive. My school counsellor was with me and had, with an unnecessary lack of tact I thought, asked me not to screw this up.

Lunch proved trickier than I thought, though. It was served during some fairly interminable speeches, and the main course was chicken breast. Now, I had never in my life eaten chicken with a knife and fork. It was surely something to be eaten with the hands if only for the sensual pleasure of it! So I had a bit of trouble. At one point, as I was making a great effort to get a bit of meat off the bone, the whole breast went flying off the plate onto the linen tablecloth. Fortunately, everyone was looking at the speakers, so I grabbed the chicken with my hands and put it back where it belonged. It was only then, with my fingers still on the chicken, that I realised my school counsellor was watching me. He shook his head.

“You can dress her up, but you can’t take her out.” The story of my life, really.

In the end, the Downey Junior Women’s Club couldn’t decide who to give the scholarship to, so they split it between all the candidates. I got a scholarship worth $600. Hardly worth getting dressed up for.

So I worked my way through college. First in an all-night coffee shop (where I used to catch a bus after work and go straight to classes after snatching a quick nap in the doctors’ on-call room at the UCLA Medical Center) and then at the UCLA cafeteria. But I was there! On that leafy campus with the old buildings where 30,000 students studied, where Angela Davis had taught philossphy and where students got beaten up for protesting against the war. Wow.

Nevertheless, UCLA was a difficult adjustment for me. I couldn’t help notices it was full of people who were not at all like the ones in Bellflower. They all seemed to have parents who were doctors and lawyers and businessmen. One guy I went out with had parents who were both psychiatrists (which might have gone a long way to explaining why he was so screwed up). A lot of the students had expensive cars, had graduated from Beverley Hills High, and one I knew even had a tennis court in his backyard! They all seemed so confident, erudite, socially-skilled; and they knew an awful lot of big words. I was gauche, inept, awkward and didn’t own a dictionary. So I would lie and tell people I was from leafy Long Beach. Not Bellflower. I couldn’t be from Bellflower.

In my first year as a Sociology major I took a class called “Social Change”. It was one of those monster lecture classes of well over a hundred students, and was taught by a thirty-year old Assistant Professor called Sam Friedman.

Sam Friedman had a thoughtful but slightly sardonic face, an already receding hairline and absolutely no sense of style. While his colleagues wore the required hip professor uniform of flared jeans, Tshirts, long hair and leather jackets, Sam wore black slacks and black shoes with a white short-sleeved shirt. He looked like he hadn’t thought to change his wardrobe since the early Sixties. Which he probably hadn’t.

Sam, unlike a lot of the “radical” professors at UCLA, was an activist. He had participated in the early Civil Rights struggle. He had been involved in breaking into the Draft Board and pouring blood onto their records (not their own blood or anyone they knew, by the way). And he was the first socialist I ever met.

He wasn’t at all like I thought a socialist would be. There was a lot of debate in the classroom and a lot of people who violently disagreed with him. He was always calm, reasonable and persuasive. He didn’t believe in censorship, he was just against the power held by the media barons.

“They should have to put their views out with mimeograph machines like the rest of us!” he said. (If you don’t know what a mimeograph machine is, you’ll have to look it up on Wikipedia.) He believed that all wealth is created through labour, physical and mental, and that as such everyone should share in it. And he believed that, though it wasn’t possible to build an ideal world, it was possible to build a much better one.

One of the term paper questions for the class was “Explain how the materials presented in this class have influenced your understanding of social change.” I built a Board Game called “The System” in which the first roll of the dice put you in a particular social class. For those with 11s and 12s, the game is about amassing wealth. For the 2s and 3s you just go around in a circle. My term paper was an explanation of how it reflected real social mobility and class. Sam sighed when I handed in the cardboard, coloured markers and paper. But gave me an A.

By that time I was taking more than a full load of classes in order to finish my degree earlier and save money. I was working twenty-four hours a week. I had so much reading to do that I had to learn to do it on the bus without throwing up. (My fellow passengers thanked me for that.) And then I got involved with a union organising campaign at the UCLA cafeteria.

Sam was an activist himself and started quietly making things happen for me in the union drive. When we needed to translate a leaflet into Spanish, he knew someone. When we needed to approach the Student Union, he knew someone. When we needed to get a demonstration together, Sam knew loads of people.

I started hanging around his office in Haines Hall a lot. He knew I was struggling with some of my classes and he always knew someone who could help me with those too. He had an incisive mind and talked sociology, history and (especially) politics with an understated passion. I’d hang around his office (how did the guy get any work done, I wonder now?) and we’d discuss the Industrial Revolution, union democracy, the French Revolution, the Paris Commune, America during the 1930s, Marxist Economics, Latin America and what the hell my class in Ethnomethodology was all about! (I still don’t know, but I ended up doing my term paper on the methodology of playing Twenty Questions. My research into this burning issue was subsequently enshrined in the university library as an example of an A paper. Go figure.) We discussed, debated, disagreed.

No one had ever asked me to analyse, take and defend a position before; and the experience emboldened me. I found my confidence growing; which on occasion blossomed into arrogance! During a lecture in my History of American Reform Movements I challenged the professor on his view of the Theory of Surplus Value, refuting his (flawed!) analysis point by point. I got a round of applause from the class and assumed my eloquence was certain to get me an A in his class. I got a B. I was learning the hard lessons of life too.

Despite my work schedule, I was becoming a bit of an academic high flyer. I made the Dean’s List at least five times. I was Alpha Lamda Delta. I was Pi Gamma Mu. (I forget what those things meant, but I’m pretty sure they were good things.) But I still wasn’t going to get my degree unless I could pass Statistics.

My mother, who worked with numbers all her life, took a very jaundiced view of statistics. She had worked for too many bosses who didn’t like it when she gave them the “wrong” answer. She had learned, when asked what “the numbers” said, to ask, “What do you want them to say?”

But statistics was a required course; required because a lot of academics wanted to prove that Sociology was a science like any other, and the only way to achieve that was to do lots of research in order to publish lots of studies with lots of numbers in them that could quantify human behaviour. Without statistics there would be no polls, no politics as we knew it, and no market research. Which I thought was a pretty damn good reason not to have them.

Nevertheless, no amount of protestation about my love of intuitive truth, and my moral repugnance at the reduction of the complexity of social behaviour to mere numbers, was going to get me anywhere. The truth was stark. No passing grade in Statistics. No degree.

My high school math had been a disaster zone. I couldn’t multiply. I couldn’t divide. I couldn’t do equations. I couldn’t calculate the hypotenuse of a triangle, or remember the difference between a circumference and a radius, never mind what pi r squared was! Cheap calculators hadn’t been invented yet. All I had was scratch paper, a pencil, and a brain like swiss cheese where numbers slipped quietly through the holes. And the moment I sat down in the lecture room and that woman started talking about the mean, the median and calculating standard deviation, I knew I was lost!

Every day I went to class it got worse. There was a new formula to memorise and a new reason to apply it. Every day I watched as the professor stood at the front, mouthing words that could have been in Ancient Croation for all I could fathom of it. I was in serious trouble.

I talked to Sam about it. This time he didn’t seem to know someone. It was hopeless anyway, I figured, because I just could not do math.

“You can do math!” Sam chided me (even having the temerity to chuckle!), “It’s only your gender and class conditioning that’s convinced you that you can’t!” This, I thought, was decidedly unhelpful. I was watching my degree circling the plughole, and all he could offer was some sort of crackpot left wing dogma about the social and cultural context of “intelligence”, no doubt referenced back to the Dove Counterbalance Intelligence Test of 1969, which had no possible relevance to the synapses that were failing to spark in my brain! I was dumb at math! Period!

Sam stayed calm and continued to insist it was my gender and class conditioning not my innate intelligence that was at fault. So I decided, in the cause of social research and because I was desperate, to sit in my next Statistics class and dare the Professor to impart any knowledge that I could actually understand.

“Okay!” I thought, “Go on, lady! Teach me this stuff! Make me overcome my ‘gender and class conditioning!’ Give me your golden nuggets of wisdom about the calculation of standard deviation!” I sat and I listened.

And after a while something very weird happened. It’s hard to explain, but….it dawned on me that I had understood something that she said. Just a little thing. But I had actually followed it.

She was talking about causal correlation. Research into house fires, she said, had found a substantial statistical correlation between size of fire and number of fire engines; with the smallest fires having fewest fire engines and the largest ones having the greatest number. It could be deduced, therefore, that in order to diminish the size of house fires, fewer engines should be sent. It was totally logical. It was brilliant. And entirely ludicrous. I understood what my mother meant: Lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Statistics could be used to prove anything to anybody. Without knowledge, there was no defence.

After that, with each passing day, I seemed to take in that bit more. I started to remember the formulae and filled countless sheets of paper with my clumsy, hopeless arithmetic. And I promised myself that, if I survived this, I would never have anything to do with numbers again.

Crunch day arrived as it had to, and I shuffled in with the rest of my class to take the final exam. They all looked so much more confident than I did, particularly the rich kids with their $500 calculators. (Bastards!) No one had thought of banning them yet, or providing all the exam students with them. I sat down. And when we got the signal, I opened my paper.

All I saw was a blizzard of numbers. I looked at my blank sheets of scratch paper. I picked up my pencil. And I cursed my agnosticism. It would have been a very good time to test the power of prayer.

Fortunately, given my appalling arithmetic, half credit was given for any answer that used the right formula but came up with the wrong answer. Which is what probably saved me. In the end I got a B. (A low B, but a B is a B.) I had survived. I was going to get my degree. And I had to concede that perhaps there was something in Sam’s crackpot left wing dogma after all.

Sam continued to have a profound effect on my thinking and I eventually became convinced by the argument for democratic control of the economy for the good of all which, I guess, made me a socialist. My mother was, of course horrified and, when I told her I was only taking everything I learned from my upbringing to its logical conclusion, she cried, “I never taught you to be a socialist!” This was true. My religion had. Just read the Eight Beatitudes.

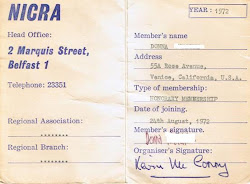

I joined the Student Worker Action Committee (a name that could only have been invented in the early Seventies!) and was even a member of the International Socialists for a while, a group who believed that one day the masses would rise and change the world. I guess they must still be waiting. When I resigned one of their number said he suspected me of being a closet anarchist. Which I probably was, and am, at heart.

When it came down to it, what I was all about for me was my mother’s struggle to provide for us; the abject existence of the cafeteria workers I stood at the steam table with; and about Little Betty who I worked with in my first job on the receiving dock of Atlantic Department Store. I still think back to that day she dithered in the canteen about whether to have the toast for ten cents or the turnover for fifteen; dithering over a nickel.

“I am so sick of being poor!” she’d said finally. When we all get sick of people being poor, maybe things can change.

2 comments:

Good one. Up the revolution. My dad was an activist for a while. I'm a lazy so-and-so, aka satirist.

I thought I'd leave a note in case you still moderate your comments. Hello from Maryland. My name is Dorie and I went to BHS with Cathie and Carol. I lived on Park St. in the People's Republic of Bellflower. Long ago and far away wasn't it?

Post a Comment