My mother was a Roosevelt Democrat in the 1930s and a Roosevelt Democrat the day she died. They used to be known as Yellow Dog Democrats because, so it was thought, that they would vote for a yellow dog if it was running on a Democratic ticket. Her mother before her was a yellow dog Democrat, married to a small farmer who was as stauchly Republican as it was possible to be. Even when the policies of Herbert Hoover ("You don't work, you don't eat") drove him to lose his farm and eventually forced him to work in a GM factory, he remained as Republican, hating the United Auto Workers union with a vicious passion and fervently believing that what was good for General Motors was good for the country. God knows how they stayed married.

Fortunately, my grandmother was a lot smarter than her husband, and managed to perpetuate a matriarchal dynasty in the family that started with my great-grandmother who was widowed at the age of thirty, and continuing through to my mother who, as a single mom, called the shots in our family. It never occurred to me that there were things women couldn't do simply because they were women, with the exception standing up to pee. (I still wish I could do that though. It would save a lot of time in public restrooms! And what about the ease with which men can pee at the side of a country road without drawing attention to themselves while a woman has to simply hold on or suffer the indignity of a highly noticeable squat? God is indeed a man.)

I grew up in a world where the fear of communism was all pervasive. Athough the infamous McCarthy hearings took place before I was born, there was a terrible sense that, at any time, soldiers might storm the Nubel movie theatre in downtown Bellflower and make us all learn Russian. The nuns told us horror stories of how, in communist countries, there were no crucifixes hung in classrooms! (Of course, there were no crucifixes hung in American pubic schools either, but let's not let facts get in the way of a good story!) We we were told that in Russia children are abducted from their parents and brainwashed and forced to spy on their parents. (I never got that one. How did they spy on their parents when they had been abducted and never saw them again?) Every time I heard an airplane flying overhead I was reminded of the countless war movies I'd seen; and I was sure we were about to be bombed. Once a month, on a Friday, the Civil Defence siren would go off and we had to rehearse for a nuclear attack at school by dropping under our desks and curling into a ball with our hands on our heads. (I'm still not sure how this was going to protect us from a nuclear strike.) Because most of all, we were terrified of World War Three. Nuclear War.

When I was eight years old we were told that the "drop drills" that we had rehearsed all those monthly Fridays, might at last be due for a live performance. It was high noon. A showdown with the Russians ninety miles from the US coastline was in progress, and Nikita Krushchev and President Kennedy were standing in a sun-baked street, staring into each others' eyes, hands ready to draw and shoot, resulting in the annihilation of the human race.

Now I thought this was unlikely, probably because my brain could not take in something as catastrophic as a nuclear war, but plenty of other people thought it very likely indeed. Our parish church was full of people who I'd never seen at Mass before. On weekdays even! People were belatedly building shelters in their backyards. The shelves of the grocery stores were being stripped of canned goods (and I thought how funny it would be if they, in their hysteria, forgot to pack a can opener) and enormous supplies of peanut butter. Now, much as I loved peanut butter, I did think being down in a hole in the backyard eating copious amounts of it might be worse than just being annihilated. But the Russians turned their ships around, the churches became pretty empty again and hundreds of thousands of people wondered what they were going to do with all that peanut butter.

That climate of fear permeated everything when I was a kid, and dissent, which I had learned in school was the Constitutional right of every American, was at every turn associated with the communists. Opponents to a war that was going on far away in a place called Vietnam were communists. The Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights movement's voter registration campaign were communists. Gay Liberationists were communists trying to bring down the family. Martin Luther King was a communist. Women agitating for equal pay were communists. I did think that, with all those communists everywhere, they must be pretty inept to not have ensured we were all speaking Russian by now.

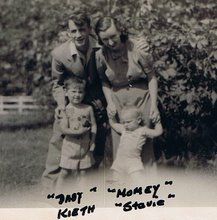

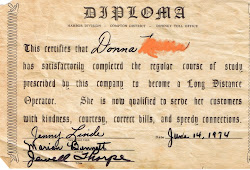

My mother never set out to be a campaigner against injustice. I think in an ideal world she would have stayed home, baked cookies and looked after her kids while worrying about what washing powder would get her whites really white. But when she had to go out to work to support a household of seven, injustice kind of found her. She got a job as an accountant in a big company, with access to all the company's books. She had been an innocent in the real world, and when she discovered that the starting wage for men doing the same job as she was doing was the top wage for women, she assumed (in her innocence) that this was a mistake. So she brought it to the attention of her boss who told her that this was the way of the world.

"Why..?" my mother asked.

"Because women don't have families to support," he replied.

"But I have four children and two dependent adults to support!"

"Yes, but generally women don't."

"But I'm not 'generally'" she insisted, "I really do have six people to support!"

My mother got nowhere, of course, and went on earning less than a man and burning with injustice.

She was an odd "campaigner". She was fairly quiet usually. Not at all strident. But had a natural aversion to privilege which made all rich people suspect until proven innocent. Her passion about injustice became part of our lives as a family. I came to never argue politics with my mother because she always won. She simply knew more about any subject you want to name than I did. As a teenager, it infuriated me! Who wants their Mom to win an argument?

She was a pacifist (who nevertheless supported the aims of the Second World War) and one of the bitter ironies of her life was that she unknowingly worked on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge Tennessee during the war, assiting the top secret develpment of the atomic bomb. When she worked for North American Aviation, she asked to be transferred from working on the Hound Dog Missile project and joined the team working on the space program which she was convinced had only peaceful purposes.

She opposed the war in Vietnam and turned a blind eye when my brother's draft dodger and deserter friends slept on our couch on their way to Canada. She agitated for equal pay as the Women's Representative at North American. Both she and my grandmother were ardent supporters of the civil rights movement. And as the gay liberation movement sarted to gather pace and I told my her that I thought that homosexuals were sick, she drawled thoughtfully, "You know, I think the only really sick people are those who can't love anyone."

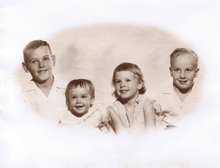

The kids in my family were raised, without our really knowing it at the time - the way kids always think their own experience is typical - to be passionate about injustice, and that is how we still are. My husband says we are the only family he's ever seen who can shout while agreeing with each other.

She was shrewd and wise and knowledgeable and articulate and never cared if anyone thought she was a communist or a communist dupe or a communist sympathiser. She was a Roosevelt Democrat in the 1930s and a Roosevelt Democrat the day she died. And I miss her.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.