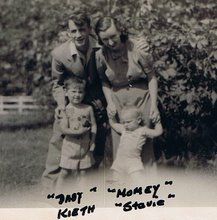

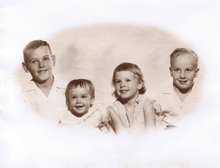

When we were kids, my sister Nancy ate so much peanut butter, my mother said that one day she’d turn into a peanut overnight. My mother was fond of these flights of fancy, and she also told me, when I toppled over my milk glass, (I’ve always been very clumsy) that The Cow was going to come to the door and say angrily, “Where’s the girl who spills my milk?” I used to say this to my three year old son when he spilled his milk, but I had to stop. It terrified him!

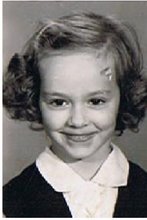

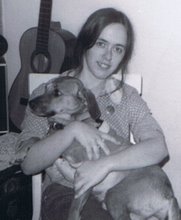

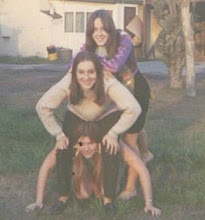

My sister did have peanut-butter coloured hair, however. And deep, clear blue eyes and freckles and fair skin that made her, after a spell in the California sunshine, resemble a tomato with leprosy. She had a trusting and unwavering belief in the goodness of people, even when my brother Steve accidentally shot me in the head with his bow and arrow. (At least he said it was an accident.) Her trusting nature got her in a lot of trouble over the years, and I came to be very protective of her, even though I was her younger sister.

The taunts our schoolmates hurled at us, that hurt me so badly and made me so desperate to conform, seemed to have no effect on her. I don’t think she even noticed; but I did. Once, when a streetwise toughie demanded a bit of my candy bar and I refused, the insult she chose to throw at me, with all the disgust and disdain she could muster, was that I was just like my sister.

“Thank you,” I said defiantly. As she walked away she spat out the Ultimate Parting Insult.

“Nosepicker!” In the prepubescent world I lived in, it was apparently OK to shake other kids down for candy, to steal, to bully, to even (like that thug Riccatone who once phoned the house to say that he was going to beat the hell out of my brother for no particular reason) resort to mindless violence. But nosepicking was not to be tolerated.(I am pretty sure that Riccatone must be in Folsom State Prison now. Or at least he should be. Either that or he’s an LA policeman.)

My sister and I had a collection of small hard plastic dolls when we were kids. They were a bit smaller than a Barbie, a doll we never owned because it was so expensive and because I was never all that interested in the idea of a doll with boobs and a boyfriend.

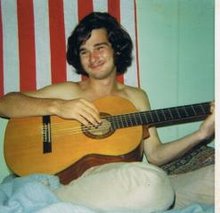

Among our collection there was a doll with brown hair and brown eyes, and another one with blue eyes and peanut butter coloured hair. The first was supposed to be me. The other, my sister. And we used them as conduits into fantasy worlds of our own creation (from which, it could be argued, I have never emerged), in which I was a successful writer and she was a famous singer.

My mother had a huge passion for classical music, and played opera and symphonies on our battered old record player, and bought us an album of “Children’s Classics” for Christmas one year and “Peter and the Wolf” another. Despite her efforts, it never took with me. But it did with my sister.

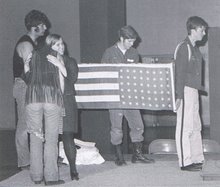

She was a gifted classical singer from an early age, and was always chosen as a soloist at high school concerts. She was, as is the tradition, an introvert with an extrovert inside screaming to get out (whereas I am an extrovert with an introvert outside screaming to get back in) and found getting up in front of an audience terrifying at first, until a professional singer gave her a winning tip. So when she came out to sing, she would acknowledge the applause, not with an inaudible, “Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”, but with an inaudible, “Fuck you. Fuck you. Fuck you.” It seemed to do the trick. We all thought she was destined for greater things.

But sometimes Fate has a cruel way of stepping in.

In the summer of my sister’s junior year in college, she went to Vienna where she saw an awful lot of opera on the cheap, buying standing room tickets on the day and doing a lot of “second acting” where she milled with the opera crowd when they came out at the intermission, and then went back in to watch the second act. She came home just before Christmas. A few months later an Austrian guy turned up on the doorstep. This was Willy.

Willy was about fifteen years older than Nancy, had a big blond beard and wore a beret. His clothes were on the bohemian side, except for the green woollen traditional Austrian jacket that he stubbornly wore everywhere, even in the heat of the California sun.

My sister had met Willy in Vienna. They had had an affair and, despite her asking him not to follow her home, he wasn’t the kind of guy to take no for an answer. This turned out to be a major character trait.

He was a rare book dealer and an artist. The main theme of his artistic oeuvre was human genitalia. Penises and vaginas, to be blunt. He drew them, painted them and sculpted them in plaster, stone and even stainless steel. He once even constructed an eight foot penis.

Now I have made mistakes with men in my time. What woman hasn’t? I lived for nearly five years with a musician who spent almost all that time we were together screwing anything with a hole in the middle. Once I threw him a surprise birthday party and the surprise was that every woman there had slept with him. And the woman I persuaded to take him out to the pub until the guests had arrived did not take him to the pub…

But any mistake I ever made was, in the power of its destructiveness, a football though a window compared with the grenade my sister threw into her life when she got entangled with Willy. He was jealous, possessive and domineering from the start. In Vienna, she later told me, she had to stare at the ground every time they were in public or else he’d accuse her of flirting with some passer-by. Nevertheless, inexplicably, she married him, with him insisting she vow to love, honour and obey, not cherish. Alarm bells should have deafened her by now.

I was living in a two room guest house at the time. It had no hallway, just the front room and a rear room off of which was the bathroom and kitchen. Nancy and Willy had no money, so I offered to put them up until they got on their feet. I gave them the front room of the house, thinking they would have more privacy that way. Willy took an almost instant dislike to me which, for my sister’s sake, I decided to ignore.

One day someone knocked on the front door when Willy and my sister were not at home. I went to answer it, which involved walking through the front room but for some reason the door to their room. There was no lock on it, and yet it appeared locked. Nonplussed, I went out the back door and walked around to the front with a key so that I could let my visitor in. Walking back through the front room from the other side, I saw why I hadn’t been able to open the bedroom door. Willy had nailed it shut! To prevent me from invading his privacy! How he had been planning to get to the bathroom was not clear.

But I said nothing about this, and nothing about the evil glances directed at me whenever he was around. Until one night, though the paper thin walls of my room, I heard Willy talking to my sister about what a scheming, manipulative and evil woman I was and I finally saw the red mist. I burst into their room, shouting like a maniac about how I was letting them stay there for free and how dare he!

They moved out the next day and Willy decided that something had to be done about Nancy’s attachment to her family and to her friends who, he was sure, were trying to turn her against him. So after that, none of us were allowed to be in the same room with her unless he was present. I did not speak to my sister alone for another seven years.

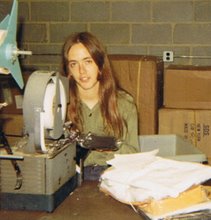

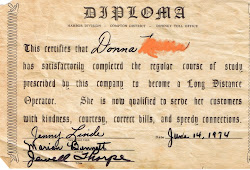

During that time, she gave up any thought of pursuing her music. She worked for the bus company while Willy stayed home and built penises and vaginas, and spent her money on rare books. The family decided not to say anything. If she was happy, that was the main thing.

But she was not happy.

Now my family, and I'm not ashamed to admit it, is a bit mad. Maybe even a lot mad. We have a streak of bipolar disorder, formerly known as manic depression, that runs like a seismic fault through our genetic geology. Research psychologists plot schematic charts of family histories, marking a black dot on every member with bipolar disorder. Our chart looks like a Dalmatian.

So, when, in the summer she turned thirty, she received a small inheritance from my father’s mother, and went out shopping, coming back with over a hundred pairs of panties and three hundred pounds worth of sheet music of ridiculous stuff she was never going to sing, I thought she was going mad. But when she then enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory of Music, abandoned all her possessions, left Willy and filed for divorce, I knew it. And it was glorious! Manic or not, I had my sister back.

We had so much to catch up on and we talked many long nights, both in London when she visited me, and in Vienna where she swiftly became very happily settled.

“When did you stop loving Willy?” I asked her.

“Oh I never loved him,” she said.

“Then why did you marry him?”

She didn’t speak for a long moment, then said, finally, “He was so in love with me. I didn’t want to be the bad guy.” All those lost years. Because she didn’t want to be seen as heartless.

Nancy was determined to make up for lost time, and she emerged from her music course determined to succeed. She had a one-woman show that made her a cult cabaret hit. She auditioned for anything and anyone anywhere in Europe, including for a theatre musical producer who told her she wasn’t raunchy enough for the part. So my sister came back with a black wig on, pretended to be someone called Gayle, and did a raunchy audition. She still didn’t get the part but the producer, who wasn’t fooled, was impressed by her tenacity.

She finally got her break when she was cast as one of the principals in the Hamburg premiere of Cats in 1986. On opening night I watched her on the stage of the Opperettenhaus, singing a mock opera duet that was greeted by an audience of eleven hundred with wild applause, foot-stamping and shouts of “Brava!” I was so unbelievably proud of her. To be here. To be doing this. Against all the odds. And I cried with joy.

But, what God gives with one hand, He often seems to take away with another. She confided in my on a visit, just before she went into rehearsals, that she’d found a lump on her breast. And it turned out not to be “nothing”.

She managed to recover from surgery before she went into rehearsals, having radiotherapy and chemotherapy during the run. She was fine for a year and then developed secondaries, still staying in the show until she finally had to move in with me in London while she had six months of further chemotherapy. On the 25th of October, 1987, aged thirty-six, she died.

When my sister was sick, she heard about a cancer support group which was being held in a classroom at a local school. She got to the school – late as she often was – but couldn’t find the right room and, by luck alone, found herself hurrying down a corridor where she overheard someone in one of the classrooms talking about The Illness. And knew she’d found the right place.

She was welcomed warmly with hugs and smiles and cups of tea and was offered a chair. It was only then that she realised that The Illness they were talking about wasn’t cancer, but alcoholism. Nevertheless, my sister stayed for the whole meeting.

“Why did you stay?” I asked her.

“They were so nice,” she said, “I didn’t want to offend them.” Nancy never did want to offend anyone.

The grief of losing her washed over the next few years of my life, and still comes to haunt me every time I hear a joke she would have liked, or something that would have made her cry, or something trivial, like a note on written in a page of a book in her handwriting. But what God takes away with one hand He sometimes gives with another. A few years after her death I was blessed with the most beautiful baby boy. With clear blue eyes. And freckles. And fair skin that would make him, after a spell in the sunshine, resemble a tomato with leprosy. And peanut butter coloured hair.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

No comments:

Post a Comment