In 1972 the consultant physicians at the Accident and Emergency Department of the Royal Free Hospital in Belfast, so I was told, had published more academic papers, and advised more doctors worldwide on the treatment of gunshot wounds than anywhere else in Europe. It didn’t take much imagination to see why.

Daily life went on. Women went shopping with their wheeled trolleys. Men went to the pub to watch football. People went to work in shops, factories and offices while others hung around the labour exchange (unemployment office) watching them jealously. Besotted couples got married. Embittered couples split up. Babies were born. Kids went to school. Teenagers went to discos. Danced. Flirted. Fell in love. As gunfire became the soundtrack of their city.

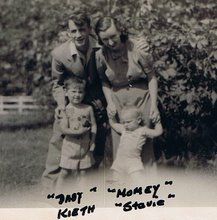

I had been in Belfast for a few weeks when I met Deirdre and Siobhan. They were about fourteen, best friends, and as giggly and gauche as I was when I was their age – four years before. They lived in the Divis Flats area of Belfast and I met them when I went to interview Deirdre’s father Eamon.

They lived in a long row of tiny two-up, two-down (two rooms upstairs and two downstairs) terraced houses with an outside toilet in the back court, and a front door opening, like all their neighbours, onto a grim treeless street.

It was not an uncommon experience among the people in these rows of houses to have an IRA man knock at the door and ask to be allowed through their house and into the back court to elude an army patrol in pursuit. You didn’t have to be a cheerleader for the IRA to allow them in. There were two reasons for this: 1) The army was pretty much universally hated and 2) Nobody wanted to mess with the local IRA. Opening that door, however could have consequences though, as Eamon discovered. The Army tore up his house the next day looking for guns he didn’t have.

Eamon was a pretty nervous guy at the best of times; the kind of guy who would never have opened his door to a Jehovah’s Witness (okay, not the best example) or a political canvasser (hmm…not much better, but you get my drift) never mind a gun-toting paramilitary. And since guns were often “found” by the army after a long and seemingly fruitless search, Eamon was pretty rattled by the experience even though all he ultimately suffered were a few broken floorboards.

(I remember a guy I interviewed being very annoyed that the army found a gun after just such a search. “If there’d been a gun there,” he insisted, “I would have known about it. I keep track.” He seemed more peeved by the suggestion that he was stupid than the arms charge he was facing.)

For some reason Deirdre and Siobhan took to me as it I were a long lost American relative (which were pretty common actually) and insisted on taking me on a tour of the area where I was introduced me to just about everyone they knew (and they certainly seemed to know everybody). I found myself constantly drinking cups of tea out of china cups and eating biscuits and telling them about life in California.

“I’ve got a cousin in California,” someone would say. “His name is Michael Healy. Do you know him?”

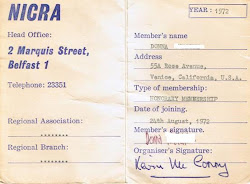

My volunteer work for the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association seemed to give me quite a bit of credibility – except for a guy who, when I told him what I was doing there, said sarcastically, “Aye, and I’m thinking of going to America to help the blacks get their civil rights!”

I told him he really should.

August 9th of that year was the first anniversary of the introduction of Internment. It was being marked by marches and protests of all kinds right across Northern Ireland, beginning with a ceremonial banging of dustbin lids at 4 a.m.

Since the Internment raids had started the previous year, whole communities would come out and bang dustbin lids on the pavement whenever a large numbers of Saracens were spotted coming into the area. It was a crude but effective early warning system for anyone likely to be “lifted”. And this was how the commemoration of the first anniversary of the raids was to begin. So at precisely four o’clock on the morning of the 9th of August 1972, every Nationalist neighbourhood in Belfast and beyond came out of their houses to bang their dustbin lids in a din that must have been heard in Scotland.

Deirdre, Siobhan and I stayed up all night and, at just before four in the morning, Eamon took us all out to watch the banging and the bonfires. It was oddly reminiscent of the Fourth of July celebrations of my childhood. I took some pictures and, because I knew the drill, always asked the subject before I took them. You never knew who you were photographing or how they would take to it! Nevertheless, flash photography always has a way of drawing attention to itself.

As we walked towards a bonfire at the end of the street, Eamon, Deirdre, Siobhan and I were suddenly surrounded by three men.

“Give us the camera!” one of them demanded. I was savvy enough to realise this was no ordinary mugging. Maybe it was the Fourth of July atmosphere, or the fact that I really wanted to keep those pictures, or because I was like a rabbit caught in the headlights and didn’t really believe this was happening. But, I politely refused to hand it over.

We were herded into a nearby house to discuss the issue with a middle-aged woman who seemed to be in charge. One of the men had already scaled back his demands and told me I could keep the camera if I turned over the film, but I continued to argue about it. I insisted that I was not taking a picture of anyone except a girl banging a dustbin lid; and that it was important that I take the pictures back to America to tell people what was really happening here.

I offered to give them the film if they would promise to develop it, at which point they would see for themselves that there was nothing incriminating on it, and give me the negatives. They dismissed this out of hand, which they would when you think about it, because they were hardly going to turn over what they think might be covert intelligence to a guy in a photo lab who might be a rabid Orangeman. Either that or they were too cheap to pay for developing it themselves.

So I opened the camera and exposed the film, explaining that I had now ruined the photos I’d just taken. But, as it was a film cartridge, the earlier shots would be preserved. Wasn’t that enough? A heated discussion followed in which one of the men suggested I might be Special Branch (the Anti-Terrorist police). Eamon, who was known to them, tried to explain that I was with NICRA and that he could vouch for me.

“Does she look like Special Branch?” one of them demanded.

“If she looked like Special Branch,” the other said, “She wouldn’t be much of an agent!” I had to admit he had a point.

Nevertheless, the woman in the house decided that the exposing of the film was enough and sent us on our way. Out in the street, in the light of a bonfire, one of the girls turned to me and asked, “Were you not scared??” And all of the sudden I realised just how inexcusably and unconscionably and recklessly stupid I had just been! (Particularly when I got the photos developed and they were all pretty crap. I’d forgotten what a terrible photographer I was.)

It wasn’t until much later, when I looked closely at the photos, that I realised there was a man (or a woman?) in one of them deliberately covering their face with their hair.

The day’s protests culminated that evening in a number of marches, one of which was from the city centre to Casement Park in Andersonstown. The park, one of the few amenities in this depressed area, had been commandeered by the army as a barracks and had caused a deep sense of grievance among the locals.

There was a carnival atmosphere as we marched out from the city centre in a blaze of placards and banners, chanting slogans and singing songs. Though I was there on my own, I was immediately welcomed into a group of protestors, along with a lanky, long-haired Australian journalist. I use the term “journalist” loosely. He was working for a magazine called something like “Psychedelic Times” that existed mainly to campaign for the legalisation of all drugs. Yeah, I know. I couldn’t understand it either. This was his very first day “on assignment” in Belfast.

Suddenly, our merry, good-natured, chanting, singing march came to an unexpected halt. Word passed down from the front that there was a police cordon across the road. The leaders had been informed that our march was banned, and we would not be permitted to go a step further.

I was surprised that everyone seemed to take this rather cheerfully. One of the group that had adopted me turned and said, “Just follow me.” So I followed him. Along with hundreds of others, including the Psychedelic Australian, I followed him over walls, along alleyways, through gates, across gardens and over waste ground. It was like a dog had scattered a flock of sheep and the farmer had no chance of rounding them up again. And every sheep arrived, defiantly, at Casement Park. (I had the feeling they’d done this before.)

There was a very large crowd at the park gates by the time we arrived. The army were out in force, ready to rebuff any attempt to storm their fort. The Psychedelic Australian couldn’t believe his luck. The prospect of “action” on his first day! I had already taken a real dislike to this guy.

Action, however, was pretty thin on the ground at that point, and the only weapon produced was the hot air of the interminable speeches that always accompany political rallies of all kinds. From the “Down With This Sort of Thing” variety, to rampant incoherent raving, nobody really listens because the beauty of a good protest march is the sense of common purpose, the camaraderie, and the outside chance of getting laid that night.

But as the speeches droned on, four Saracen armoured vehicles were positioned on one side of the crowd, and four more were positioned on the other. The atmosphere was becoming tense.

It had been a year since Internment without trial had been introduced; a year since the army first arrived into people’s homes at four in the morning and had taken away husbands, brothers and sons; “terrorist suspects” who usually turned out to be nothing of the sort. And it had been barely more than six months since fourteen unarmed anti-internment protestors had been gunned down in Derry. It wouldn’t take much to turn the previous carnival mood ugly. And “what it took” arrived swiftly.

The light was fading, the rally was ending, and we were asked by the march organisers to head home peacefully. It was then that the four Saracens on both sides of us began to advance at a slow, steady pace towards us. With the heavily protected park gates in front of us and armoured vehicles on both sides of us, we were caught in a pincer movement and were being shown the door. A few lads started to throw stones at the advancing Saracens.

“This would be a good time to leave,” I said to the Psychedelic Australian. He was having none of it.

“Leave?” he said excitedly, “This is what I came here for!” Some lads (in a tongue in cheek way, I thought) invited him to throw a few stones with them. You’d think he had just been invited by a native Bajan to swim with the giant turtles! And off he went.

By this time many in the crowd were surging forward in response to the army pushing them back. I don’t know a lot about physics, but I knew this was not a good thing. I started to move through the crowd in the opposite direction, trying to get out through the only escape route. I saw youths carrying milk bottles to the front of the crowd and breaking up flagstones. It was turning into a stand-off as defiant protestors formed a solid and unmoving mass in the face of a wall of Saracens and riot shields. It was impossible to get through the centre of the crowd so I found myself moving to the edges which was only dotted with a handful of less strident protestors. It was nearly dark now.

Suddenly, I heard a roar from the crowd. It all happened in a few seconds. The army rushed forward as determinedly as the crowd pushed back. A light caught my eye. And, like Lot’s wife, I turned around to see what it was. A petrol bomb flew through the darkening sky, crashed to the ground, exploded, burned; casting an eerie glow onto the looming bank of Saracens and bringing the black silhouette of a stone-thrower into stark relief.

I saw three pinpricks of light flash just beyond the flames. I heard three dull pops. In the split second it took for me to register that one of those pinpricks of light was directly in front of me, I felt something hit me in the stomach – hard. And I fell to the ground, doubled up and unable to breathe.

It was surreal. The army were charging and people were running and screaming. I could see feet running past me. And heard more pops. But I couldn’t cry out because I couldn’t breathe. Suddenly there were two or three people kneeling around me.

“You’re alright! You’re alright!” someone said, “It was just a rubber bullet.” Out of nowhere, a St. John’s Ambulance crew had arrived.

The crew seemed to work the riots in Belfast the way the crews in more peaceful cities work the football matches. And they had a drill for just the eventuality I had found myself in. The most important thing was to get me out of the way of unfolding events; first because I might incur further injuries; and second because, since the army would only shoot a “ringleader”, then I must be one and would be liable to arrest. But before I was rescued, I wanted just one thing. “The bullet!!” I cried, “I want the bloody bullet!”

I was picked up by a guy who was understandably unimpressed by my priorities, and carried into a house nearby. It was full of strangers who seemed to accept the intrusion with something bordering on insouciance, as the riot raged on outside us.

My rescuer introduced himself as Des and laid me on the settee in the sitting room.

“Thank you,” I said.

“You alright?”

“Yeah,” I said, “I just wish I’d got the bullet.”

Well, I can’t fault Des’s bravery or devotion to duty because, bless him, he actually did go out amid the chaos of charge and counter charge, and tried in vain to find the bullet that hit me. It had, rather miraculously, hit me in the stomach exactly where I was wearing a heavy leather belt, and would leave no more than a strange little cross in my skin at the point of impact, and a large bruise.

After awhile the confrontation outside passed by like a rampaging tornado and then petered out like one too. When it was safe, the occupants of the house were thanked and I was taken to a community centre which was full of the walking wounded. People were exchanging opinions about what happened, to whom, where, and who got the better of whom. Des seemed to know everyone there and, as they swapped stories, he told his own.

“And then,” he said, “when she finally got her breath, she said ‘The bullet! I want the bloody bullet!” He went on to tell them how he went out looking for it in the midst of the mayhem outside, but couldn’t find it. “If I’d found any bullet! Any bullet at all,” he cried, “I would have gone back and told her it was hers!” He laughed, and the others laughed with him.

A boy of about thirteen who had been listening piped up quietly.

“I picked up the bullet that hit you.” He held it out to me. “Do you want it?”

When I was a kid, we collected glass bottles from neighbours and turned them in for the deposits on them. It was how we earned our pocket money. Kids in Belfast earned their pocket money by collecting rubber bullets and selling them to journalists. So, though moved by his offer, I said I couldn’t take it.

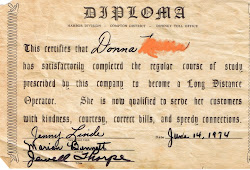

“But since it hit you,” he said, “I think it’s only right that you should have it.” He borrowed a ballpoint pen and wrote on it: “Witness that this bullet hit Donna”, signing it “Liam Connolly”. And he put it in my hand.

A few hours later when all was quiet again, Des gave me a lift back to my digs. “I hope you’re not getting the wrong impression of us,” he said.

“Not at all,” I replied, “Everyone has been very kind to me.”

“Aye,” he said, with a certain sadness, “Belfast would be such a lovely wee place if people would stop killing each other.”

History is full of “what ifs” I guess. What if the early civil rights movement in Northern Ireland hadn’t been so brutally suppressed? What if the British Army hadn’t shot down fourteen people in Derry on Bloody Sunday, driving nails into the coffin of peaceful resistance, and providing such an effective recruiting tool for the IRA? What if the two communities hadn’t become so violently polarised? What if the power sharing that has now begun in Stormont in 2007 could have been achieved without bloodshed in 1970? What if all those people who died in all those years were walking around right now, leading unextraordinary lives?

In 1998, shortly after the Good Friday agreement was signed and four years after the IRA and Loyalist ceasefires, I was adapting a book for BBC Northern Ireland in Belfast. The city I encountered after twenty-six years was nothing like the one I remembered. It was full of smart restaurants, wine bars and pubs. There were no boarded up shops announcing their “Grand Bomb Damage Sale”. No gunfire crackling in the background or the dull thud of a bomb exploding somewhere across the city. Even the much besieged Europa Hotel, where I stayed, was unprotected by concrete bollards, barbed wire and blast shields.

In a taxi on my way to the Aldegrove Airport in the dark early hours of a winter morning, the driver asked me if I’d ever been to Belfast before. I told him I had. In 1972.

“That was a terrible time,” he said.

“It was,” I replied.

I looked up into the cloudless sky and, for the first time since I was a kid, saw a shooting star. I hoped to God that this was a good omen.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on "Post a Comment" below.

1 comment:

"Where is Liam Connolly?" - go on do it!! I can see the book cover now! Was lovely to meet you the other night, you're great craic as they say back home. Sara x

Post a Comment