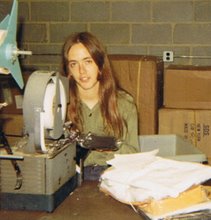

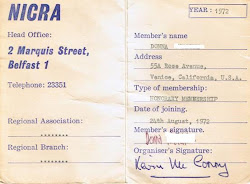

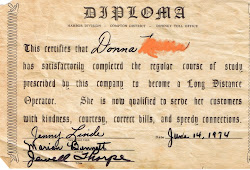

The first time I went mad, I was eighteen years old. I was in my first year at UCLA and taking a full load of classes. I was working twenty-four hours a week on night shift at a twenty-four hour coffee shop. I found I didn't need something as mundane as sleep when there was so much out there to do. I had discovered playwriting and politics and sex. And boy, oh boy, had I discovered sex! Having been a good Catholic girl a year before, I was getting laid as often as most people shake hands, and with as much tenderness or feeling. In fact the whole thing had become no more than a wet handshake to me and, had it not been the era of Free Love, I might have been carted off on charges of Leading an Lewd and Immoral Life. I was on top of the world. I was having the time of my life. I was convinced I could do anything. And I was having a hypomanic episode.

Then came the crash. I ended up at Student Health, where they decided I was a danger to myself and referred me to the Neuro-Psychiatric Institute on campus. Who put me into Group Therapy.

At first, I wasn't amazingly keen on the idea of group therapy. It seemed like a way to economise on psychiatric care; two shrinks taking a whole bunch of patients at the same time. I wanted my own shrink! To listen to me drone on interminably about my childhood and dreams and that kind of stuff, like you saw in those films like "The Three Faces of Eve". But it was take it or leave it so I took it.

Group therapy was taken by two trainee shrinks; Alan and Dave. Alan was a research psychologist retraining as a clinical psychologist. He was intense looking with deep brown eyes that looked bovine enough to make you think he really cared. Dave was blond, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and looked the very soul of sanity. Of course, if you know anything about the kind of people who become shrinks, you'll know this could not possibly have been the case.

The group therapy room had a small circle of plastic chairs in it, and one wall was covered by a large mirror. It wasn't a mirror, of course. It was two way glass and Alan and Dave were being observed by their Professors who were also observing us. Weird, huh?

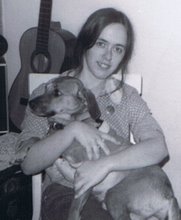

But not as weird as the group itself. There was Sasha, a woman in her late twenties who had recently been released after eight years from the Camarillo State Mental Hospital and who suffered from schizophrenia. There was Marilyn, a teenager who told us that whenever she looked into the mirror she saw a fat person. I had never heard of anorexia before and it seemed an odd thing to have as a mental health problem. There was Louis, a balding man in his late thirties who stared at his hands and wrapped his feet around the chair, and who would definitely not have been there were it not 1972. Louis's "mental health problem" was that he was gay. And there was Paul.

Paul was just about to turn twenty. He heard voices and had been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. Paul had done a lot of psychedelic drugs in his life, but no one thought to ask, back then, if the drugs were causing the symptoms. So he was admitted as an inpatient and given a whole lot of Stelazine, a major tranquillizer, which made his eyes glassy, his talk slow, and his limbs shaky.

All in all a freaky little group. And I loved it! Here at last was a group of people who I could relate to! Who wouldn't think I was weird! We bonded almost immediately, treating sessions like social occasions and, early on, decided that we wanted to have coffee available to make things cosier. When we were told that catering would not be possible because of bureaucratic hurdles, I brought a coffee pot, coffee, cream and sugar to the next session. The shrinks struggled for control but found themselves overwhelmed by the group dynamics. (Wonder what the Professors behind the glass thought?) Having been desperately lonely in the Outside World, group therapy became my refuge.

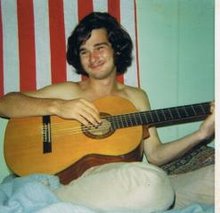

Paul and I became good friends through the group. He didn't get a lot of visitors, as the hospital was about seventy miles from where he lived. I was on campus all the time, so I took to visiting him every day. His was in a locked ward (which I think they all were then)and they had a pass system in operation. Level 1 meant you had to stay on the ward. Level 2 meant you could go out into the rest of the hospital even, oh thrill of thrills, to the cafeteria and have coffee. Level 3 meant you could walk around outside the hospital and Level 4 meant you could go home on a three-day pass. Paul was on Level 1, so we spent a lot of time hanging around the ward talking and playing music. He was a very fine musician.

Paul's previous psychiatrist had committed suicide, which is never a very encouraging situation when this is the person who has been trying to make you better. Paul's case was taken over by a Famous Shrink who made it clear that, because he was a Famous Shrink, he was only taking on Paul's case temporarily as he had other cases to deal with that were much more likely to get him published in academic journals. Okay, he didn't say that, but it seemed to be the subtext… Paul took what I thought was a perverse delight in being referred to a famous person.

Meanwhile, group therapy had become like an elaborate and traumatic game of strip poker. We drank the coffee I brought from home (Paul took charge of the coffee pot since he was in residence at the hospital), and bared our souls and occasionally wept and even hugged. (Not me, though. I'm not really much of a weeper or a hugger.)

Sasha finally broke down and talked of the terrible abuse she had suffered at Camarillo State Mental Hospital and the damage it had done to her and other patients there. Dave put his hands together as if in prayer in front of his face and gently challenged her to admit that the abuse she believed she had suffered was not real and only "part of her illness". Well, maybe Dave didn't believe her, but I did. Of course, having an anarchist streak in me, I'm a sucker for anything that dishes the dirt on authority. Four years later, three doctors and five other employees of Camarillo State Mental Hospital were indicted by a grand jury in California in connection with the deaths of two hospital patients, and against a background of suspicious deaths stretching back several years.

I liked Alan though. He had an incisive mind and was canny enough to know that the bond the patients felt for each other was not a conspiracy against the staff. He took my anarchist outbursts in his stride and eventually described me as an armadillo with a raw and inflamed innards. Yeah. I like to think so too.

Paul, I discovered, wrote the most amazing, witty and soulful songs, that could make you laugh one minute and cry the next. He wasn't just a guy with a guitar, he was, I realised, very special. He wrote a song for me, which I never recorded or made him write down. But I do remember this bit of it:

She has sympathy and sense,

She has calm and confidence,

Roses and a barbed wire fence,

Payments, mortgages and rents

But by and by

With the ease of gently washing tide.

She'll be fine.

I started to encourage Paul to take his music seriously. He wrote more and more stuff, his tunes and his wit and his poignant reflections on life hitting home more acutely each time.

Paul eventually got to Level 2 and we started to go out into the hospital, hitting the cafeteria and the UCLA Medical Center library. This was a favourite place for Paul because he could finally look up the side effects of all the drugs he had been put on. The last side effect listed for any drug you want to name is "Death". Even aspirin. If you don't believe me, look it up!

I had started to worry about Paul, though. He had an easy going personality that seemed all too easy to manipulate, even unwittingly. The nurses on the ward had been used to Paul being on the ward when he had been on Level 1. Now, whenever I came around so that we could go out, there always seemed to be a nurse saying Paul can you clean up your room? Paul can you take this to the pharmacy for me? Paul can you drop this off at reception? He felt he was being treated like a child, but never said anything. Anarchist that I was, I tried to school him in the ways of teenage rebellion.

"Look!" I said, "Repeat after me. I am not going to take any more of this bullshit!"

I got him to repeat it several times and occasionally he would even say to a nurse, "Would you mind if I do it later? I've got a visitor." It was a start.

By the time Paul got onto Level 3 and could walk around outside the hospital, he was in rebellious mood. He even asked me if I could bring a joint for us to smoke on my next visit. Which, in the cause of youthful rebellion, I did; and we got pleasantly and hilariously stoned. I remember that day and everything about it. It was glorious! We walked around in the sunshine, giggling like naughty school kids until it was time to go in. We found ourselves walking down a corridor and realised we were outside the group therapy room. It was empty. We went in and looked at all the empty chairs and decided to make it into a short play! We leapt from chair to chair, impersonating Alan and Dave and Louis and Sasha and Marilyn and the rest; and realised what an absurd proposition group therapy really was! We just couldn't stop laughing.

But things were to get serious all too soon. His father came for one of his rare visits and Paul couldn't wait to tell him all about his plans to take music seriously when he got out of the hospital. But his father was having none of it.

"Grow up!" he told him, "You're not going to earn a living with all that! Get a grip on yourself, for God's sake!" Paul was devastated. And no matter how much I tried to get him to say, "I am not going to take any more of this bullshit", I got no response. I was furious with him. How could he let himself be beaten down? How could he be such a wimp?

And then he went to see his Famous Shrink who told him some good news. He was going to make Paul one of his long-term patients. Just think! Paul might eventually get an article in an academic paper devoted to him! But he didn't want to be a long-term patient. He wanted to be well. And somewhere in there, his spirit broke.

We fought a lot after that. And then we drifted apart. I stopped going to group therapy. I felt better, I thought. The ritual of my separation was the collection of my coffee pot which Paul had been bringing to sessions. I never saw him again.

A year later I was working on campus at the student union cafeteria, dumping ladles full of hot chilli and soup into bowls; and I looked up and saw Sasha. She was a student now – majoring in psychology.

"Do you ever hear how Paul's doing?" I asked her.

"Didn't you hear?" she asked.

I didn't like the way she glanced away from me when I said no. I didn't like the way she paused before she spoke. Several months before, she told me, he'd taken an overdose. Then, changing his mind, he'd called an ambulance. But he had emphysema; his lungs were not good. He stopped breathing and they couldn't resuscitate him.

Paul died of an attempted suicide. He was twenty years old. And all his astonishing talent died with him. I suppose it's natural in those circumstances to wonder if you could have been there, could have done something, could have said the right thing. I certainly thought about that. And for a very long time.

Within two years, I would try to end my own life too. But, more by luck than judgment, I would survive. I would fall in love. And fall in love again. I would emigrate to Britain. And buy a dilapidated house and fix it up. And raise a son. I would become a writer. And have successes and failures, joy and grief. Paul would have none of those things.

By and by, with the ease of gently washing tide, I'd be fine.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

1 comment:

I am absolutely riveted. I certainly hope this blog is part of, or will take the shape of a manuscript.

Post a Comment