The one thing I wanted from a university education was to be taken seriously. The Theatre Arts Department at UCLA was never going to do this for me. It was full of people who wanted to be stars in Hollywood and who squealed with delight when they were called in for an audition for a bank commercial. So I had decided to study Sociology. And by the end of my first year, I decided that I would eventually stay on to do a PhD and become a Sociology Professor. How much more serious can you get?

So I don’t think I was really prepared for it when Lari Pittman moved in.

Lari was an exceptionally talented artist who had gone to high school with me. He had been part of the “avant-garde set” who lived as though they were living in Paris just before the First World War. They wrote beatnik poetry and played blues and edited a magazine called “Implosion” and created art that defied convention and often shocked. (One sculpture I remember, which was done for a Religion project, was a statue of a saint with the head broken off, with red paint – blood – pouring from the neck. We were a liberal school I guess. No one got expelled.) I desperately wanted to be part of that set at the time. But my poetry was doggerel, I didn’t even know what the word implosion meant, I sang mournful folk songs (badly!) while strumming a guitar (even worse!) and drew pictures of troubadours in art class (don’t ask – I can’t even remember).

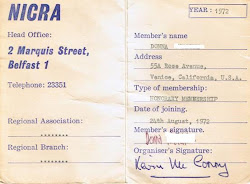

Lari came to study art at UCLA and in my second year there, he became my roommate at 55A Rose Avenue in Venice. Venice (California not Italy!) was on the beach and was then a neighbourhood full of hippies, students and elderly Jewish ladies who ran bagel shops.

55A Rose Avenue was a tiny ramshackle clapboard house that had been the servants’ quarters of the big house in front from the time when people had servants. (I have no doubt it has long been bulldozed to make way for the endless acres of the condos that came later.) It had only two rooms, with a tiny kitchen and a bathroom tacked on, a wooden porch out front, ancient linoleum floors and no heat. (When we told the landlord we really needed a heater he said, “This is California! What do you need a heater for?”)

When Lari arrived in the life that I was trying to build for myself – serious, intense, intellectual even! – it was like I was one of those crazy people who goes out to film a cyclone. And those crazy people, as we know, sometimes don’t manage to keep the distance they’d planned.

He seemed devoid of any inhibitions and was fond of shouting out to the people in Mercedes-strewn Westwood from the window of his Pinto. He berated a cyclist for riding in the middle of the road Continental style.

“Cest ne pas Europe!” he’d ranted. And, on Halloween, he drove alongside complete strangers and shout like an overgrown ten year old and shouted, “Hey, is that your face or is this Halloween?” (Actually, I pointed out to him, the joke goes, “Is this Halloween or is that your face?” He never did get it right.) Discovering a couple of stale Twinkies in his car, he did a tour of the UCLA parking lot to find the most expensive to smear them on. (If you once parked an expensive car in the UCLA parking lot in 1972 and returned to find it smeared in Twinkies, I apologise on his behalf.) And once, when we were stuck in traffic next to an absurdly expensive sports car, Lari rolled down the window, put his hand under his chin, looked at the driver with stars in his eyes and purred, in the sweetest voice imaginable, “Hey mister, are you really a millionaire?” I was amazed and not a little embarrassed by these outbursts, but also fascinated by them. Lari, I discovered, did not spend a lot of time trying to be taken seriously.

But he was someone to be taken seriously when he was feverishly creating art in the front room of 55A Rose Avenue. His work seemed to occupy two extremes. He etched exquisite screen prints of leaves and plants created out of thousands of pin prick scratches; and also painted enormous canvasses composed of bold grids full of the most delicate of images. He worked in greys and browns and creams and autumn pastels. And when one of his art teachers forced him to work with a more strident colour, he painted one small corner of the grid yellow, which made him dance manically through the house singing “Congratulations! He’s using yellow!”

I fell in love with one of his “grid paintings”, but he wouldn’t have let me buy it even if I could have afforded it. (He reckoned he could get $300 for it, a fortune for a poor student.) He was not ready to exhibit. He stored his paintings in his mother’s garage and, because she was very proud of him, she would hang them in her living room. He would come home for a visit and put them back again. When he left, she would put them back up again.

He remained quietly worried, though, that he wasn’t developing fast enough. He felt he had to make his mark before he was twenty-three, or sink into obscurity…

Now, one of the requirements of every degree taken at UCLA was to complete a certain number of Breadth Requirements. These were courses taken outside your own area of study that were intended to add Breadth to your degree. To most of us, however they were a chance to amass as many subject units as possible with easy classes: like Field Biology, or Dum-dum Biology as it was known, where all I had to do was go on field trips and identify plants and humanely captured rodents like the Peromyscus Californicus. (California Mouse. Like I said, it was an easy class.) And I had to know that science could not explain why the bumble bee could fly because it was aerodynamically impossible. I also took Playwriting. And, at Lari’s suggestion, the History of Modern Art, taught by Dr. Kaiser.

Dr. Kaiser was then Professor Emeritus in Art History at UCLA, and he must have been at least eighty because Lari told me he had been Picasso’s art dealer in Paris during his Cubist Period. In his suit and bow tie, there was something of an old-fashioned grace about the man. During the Student Strike the previous year, a group of students had burst into his lecture chanting, “On strike! Shut it down!”

“Please,” he had said in his heavily accented but quietly dignified voice, “If you must disrupt my class. Do it with elegance!”

The History of Modern Art was a popular course, and was held in an auditorium to accommodate the hundreds of students who enrolled, hoping for an easy class that they could ace.

But Dr. Kaiser was fiercely passionate about art, and disdainful of the students whose eyes were on their notes as they wrote down everything he said, instead of looking at the art he was showing us up at the front.

He was, to those who looked up from their notebooks, incredibly charismatic. As he talked of the artists and their work, it was as if he had been there himself (which he probably had.) Showing us a series of Modigliani’s sleepy looking nudes he said, “To look at these paintings you would almost think he had been sleeping with them. He had.”

These artists and their work, I realised, were reflecting their own time, both personally and historically; like the Dadaists who, when confronted by the rise of Nazism dressed in the clothes of patriotism and high ideals, put a urinal on the wall and called it a “Fountain”.

Meanwhile, my life with Lari was becoming increasingly insane and wonderful.

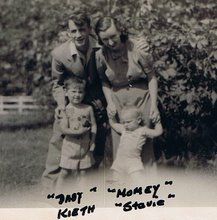

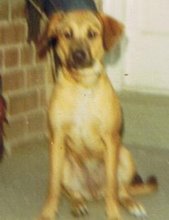

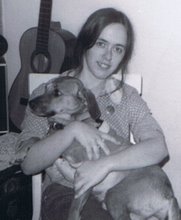

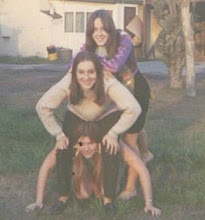

We took to dressing up my dog Gimbol (whose name had been changed from Methedrine for obvious reasons. You try calling a lost dog by shouting “Methedrine!” in a neighbourhood that was then full of drug addicts!”) in ridiculous clothes, and driving around pretending she was our daughter.

When she was in heat, there was a dog who came courting every day. We called him Roger, which we thought was a good name for a suitor, and he camped out on our porch, visibly mooning, for days. Eventually he and Gimbol eloped (the back door hadn’t been closed properly one night) and we found ourselves having to build a nursery for her out of a very large packing crate which we lined with baby wallpaper, and decorated with yellow bows. (Roger, predictably, refused to stand by her and disappeared, leaving Gimbol holding the puppies!)

We found an old rug and some abandoned furniture in the alley outside and set up a “room” on the vacant lot next door. A drunk stumbling by thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever seen. Everyone else averted their eyes, thinking we were bonkers, which of course we were.

We made countless chicken dinners and sat on the wooden porch pretending to be “hicks” and exchanging dialogue (loud enough to cause the neighbours to curse us) all of which had to rhyme with Ed.

“Did you hear about Fred?”

“He got wed!”

“No you’re thinking of Ned!”

“He went to bed!”

“No, he’s dead!”

“Fred’s dead?”

“No Ned!”

“That’s what I said!”

It made no sense at all. And I found myself celebrating my lack of seriousness.

As the term drew to a close, Dr. Kaiser was increasingly frustrated by the students who had spent the past three months looking at their notes rather than the art.

“Many students have been asking me,” he announced at the beginning of one of the last classes before the final exam, “What I want you to memorise for the exam. So I am going to tell you.” A din of rustling papers and of pencils and pens being retrieved greeted his announcement. He paused. Pencils were poised above notebooks. “I want you to memorise every art movement, every painting, every date, every artist, what their grandmothers ate for breakfast…” Some students looked up quizzically, but the dim ones kept on writing. He sighed. “I do not want you to memorise anything. I want you to remember it. I do not memorise the moment I kissed my first love!” He seemed suddenly wistful. “But I remember it!”

Slowly, I had began to doubt my resolve to become an academic, to get a Phd in Sociology, to spend my life in research and teaching, to be taken seriously. What I wanted, I now knew, was what I’d always really wanted and had dismissed as unachievable: to become a writer.

Lari moved out the following year to study at CalArts. Before he left he gave me a shadow box of an exploded clock he’d created in high school. It has always hung above my writing desk.

He went on to become a well-known artist and has exhibited all over the world. I reckon some of the hits I get on this blog will be people who have googled his name and accidentally ended up here.

I wonder if he remembers driving around West LA with Gimbol dressed up in her evening wear or her “Gypsy look” complete with headscarf.

“You buy her all these clothes!” he had admonished me in a crowd once, “But I have yet to see a decent pair of shoes on her feet!”

No comments:

Post a Comment