If there was anything my mother missed about Chicago when she moved us to California in the Fifties, she never expressed it to me. Chicago was a beautiful city of great architecture, but she seemed unmoved. It was the home of jazz. So what? And it had seasons. California only seemed to have one season. Round about January, the leaves would abruptly fall off the trees and quickly grow back before anyone noticed their embarrassing nudity. My mother, when pressed, would concede that, yes, California did not have real seasons, without the slightest sense of regret. Mainly because, in Chicago, they had real winters.

I understand that in Chicago, there are winter days that are so cold that the hairs in your nose can freeze before you walk fifty yards. This impresses me because my nose hairs have never frozen under any conditions and I am left to wonder what that feels like. And apparently in Chicago it also snows a lot.

The one thing my mother seemed to miss the least about Chicago was snow. She had had her fill of shoveling the stuff, putting chains on the car, falling on her ass on the ice, and dressing kids up in snowsuits, galoshes and mittens only for them to go out for ten minutes and want to come back in again. So, when her brother Gene offered to take my mother, my brothers, my sister and I up to the “snow mountains” to play, my mother told him she was washing her hair that year, but he was welcome to take us if he wanted. So he did. Four kids. My uncle is a saint.

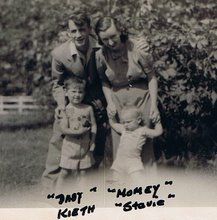

It is one of my earliest memories, but I can remember getting kitted up in the Chicago snowsuit and galoshes (that I probably grew out of by the end of the day) and going off to build a snowman, have a snow fight and then want back in the car after ten minutes. (Some things, as my mother could have told Gene, never change.) I think it must have been on this trip that my brother Keith embarked on his love affair with mountains, snow and ice.

As soon as Keith got his license at the age of sixteen, the call of the wild, the proximity of mountains covered in snow and the availability of my mother’s Ford Galaxy station wagon was irresistible.

Skiing, of course, was out of the question; and was about as likely for a group of ragged kids from Bellflower as yacht racing. (In any case skiing has always seemed to me a very expensive way to break your leg. It is so much cheaper to buy a ladder and then fall off. If you borrow a ladder, it’s even cheaper.) So one day my brother brought home a four-man toboggan.

For the price of a tank of gas, we could kit ourselves up in layers of ordinary clothes and shoes, putting plastic bags around our socks to keep our feet dry (which never worked), drive up to Wrightwood and stop by the side of the road wherever we spotted a good toboggan hill, climb to the top and careen down the hill at a speed that would have made my mother, had she seen us, call a halt to the whole thing. But she wasn’t there. Obviously. Theoretically, you can steer a toboggan by lifting the curl. And theoretically you can brake it with your feet. Neither of these things are true. We ran into a lot of trees.

One evening, as we were returning from a particularly good run that we’d found that day, that required us to bail out at the bottom before we hit a road full of passing cars, there was a major hitch. It was starting to snow and a ranger, anticipating a heavy snowfall, had closed the road and there was a locked metal gate preventing us from getting out and getting home.

For some reason, this didn’t alarm me at all and I thought it would be a great adventure to sleep in the car all night. Keith was not enthusiastic about the idea. First of all, the heat in the car would run out as soon as the engine was switched off and the engine would switch off as soon as the gas ran out. And secondly, if the snow reached the tailpipe, exhaust would enter the car and we would all be found dead the next morning. Keith always had to ruin everything by being practical.

So he got out of the car and hiked down to the ranger station to get someone to come and unlock the gate. The ranger station was closed, however, so he hiked back again and had a good look at the gate.

“Well,” he drawled quietly, “I think we’re going to have to break through the gate.”

Finally! An exciting climax to the adventure. We were going to accelerate into the barrier and smash through it at great speed like in a James Bond film. Sadly, this was not what my brother had in mind. He inched up to the gate until the bumper touched it. Then he revved the engine gently until there was enough force on the padlock to break it. And we were on our way. Not quite James Bond.

I didn’t discover the meaning of the words “laconic” or “taciturn” until I bought a dictionary and I didn’t own a dictionary for a very long time. My mother-in-law once asked me how I could be a writer and not own a dictionary.

“I use short words I can spell,” I replied. (I wouldn’t mind that being written on my gravestone. I still use short words I can spell. It’s just that I also do crosswords now and, as everyone knows, you can’t do crosswords without a dictionary.)

Keith, I discovered from the dictionary, was both laconic and taciturn. He was quiet, self-contained and kept his own counsel. Another way of looking at it was that he was uncommunicative, unemotional and stubborn. That’s kind of how I looked at it as a kid anyway, particularly when I was having a tantrum at him and he just quietly went into the bathroom, closed the door in my face and locked it.

So when he announced at the age of eighteen that he had signed up for the Air Force, it came completely out of blue – or out of the Wild Blue Yonder, as it were. (Alright, I can hear you groan at that one.) I guess, with the Vietnam war escalating, he figured he’d join the service before he got drafted.

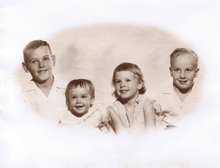

He was the first of us to leave home and it was quite a shock. The prospect of there not being seven of us living together in our house in Bellflower had not occurred to me before.

The Air Force soon realised my brother was a very smart kid and started training him intensively in electronics. My brother Steve, who knows about stuff like this, said he achieved the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree in electronics in less than eighteen months. So intense was his training, in fact, that he was not given Christmas leave that first year.

We were a very close family and the idea of a Christmas without Keith was unthinkable. So my mother, my brother Steve, my sister and I boarded a Greyhound bus for the fifty-two hour journey to Biloxi Mississippi where my brother Keith was stationed.

It was a trip that could only be described as a modern reinterpretation of Dante’s journey into Hell. We were woken at three o’clock in the morning to get off and sit in a freezing terminal in San Antonio so the bus could be cleaned. Steve got food poisoning from one of the Greyhound cafes on route. And Texas just went on and on and on and on and on.

We spent Christmas in a Biloxi motel in the warm glow of a small, spindly tree decorated with paper ornaments, and had our dinner in one of the only restaurants in New Orleans that was open on Christmas Day. I had coffee for the first time to show how grown-up I now was. (I was twelve.) It was half milk and I shovelled about half a cup of sugar into it. My brother seemed subdued that day, but he didn’t talk about it. He never talked about it.

We were delighted when we heard that Keith wasn’t going to be sent to Vietnam. He was being sent to the Middle East which, to us then, was just a place where there was a lot of sand and camels. I didn’t even know there was oil there; I thought that was all in Texas.

I was never clear about what happened next. He was apparently recruited into Intelligence and was given a Secret clearance. I guess if anyone knew how to keep secrets it was my brother Keith.

Then, about a year later, my mother packed us all in the Ford Galaxy station wagon and told us we were going up to Travis Air Force Base in Northern California to visit my brother. He was in the hospital. And what I discovered when we got there was that he was in the psychiatric ward. Something had happened and my brother had snapped.

The person we visited was my brother but not my brother. He talked even more slowly than usual, when he talked at all, and his eyes looked glassy, the quick intelligence having disappeared somehow. He was drugged up to the eyeballs on Thorazine.

He was eventually given a medical discharge and came home and never talked about what happened. But there was a lot that was not right. After getting the equivalent of a college degree in electronics, Steve told me, Keith couldn’t even get past Ohm’s Law. Whatever that is. Sounds like something you’re supposed to know. Like the definition of a sentence if you get your degree in English. (That wasn’t a sentence by the way. No verb.)

He seemed to crack up on a regular basis after that, and at those times his stint in the service seemed to haunt him. He would be convinced that the CIA was after him and that the Red Chinese had broken into his house and taken things.

My brother, we later discovered, was bipolar, manic depressive as it used to be called; just like my father and like my sister who once stayed with us when her marriage was breaking up and bought a hundred pairs of panties over a period of a few days and the sheet music for about three hundred songs she was never going to sing. (Why does a classical singer need the music for the Whiffenpoof Song? “We are poor little lambs who have lost our way. Baa, baa, baa!”) By the time I was diagnosed as bipolar there was no denying that mental health was not my family’s genetic strong point.

When I brought my soon-to-be husband Richard home to meet my family many years later, I was more than a little worried what he would think. He was from a nice middle-class English family and I could only hope that my family would appear sane for a couple of weeks, or at least house-trained.

Shortly after our arrival Keith asked Richard if he’d seen John LeCarre’s spy mini-series “Smiley’s People”. Rich said that he had and then Keith asked, more quietly, if he remembered the “scene in the bank where they do the switch”. Well, he didn’t remember the “scene in the bank” but said he did because he was a polite middle-class English boy. My brother leaned over to him conspiratorially.

“That’s how they really do it,” he said.

Between my sister’s panties and my brother’s “scene in the bank” there was now no hope of convincing Rich my family was sane. He was later to discover I was a raving lunatic myself. He seems to have taken it all in his stride however and adores them. (Quite right too!)

My brothers were always close but, though I dearly loved Keith, I never knew him. He was always distant somehow and had seemed to like it that way. This grieved my mother. She really wanted us to be close.

“He’s got such a good heart,” she’d say, “He feels things very deeply.”

My brother’s love of all things icy continues to this day. He ice skates and has done competitive ice dancing all over the States. Just after my mother died, Keith fell badly on this ice, broke seven ribs and ended up in intensive care.

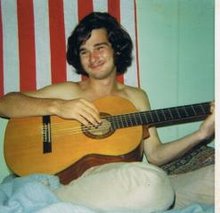

When he came out of the hospital something very strange started to happen. He started to talk about his life. He started to talk about his feelings. He came over to Scotland for my fiftieth birthday and we sat talking over a pint in the pub until my son phoned to ask when the hell we were coming home. He helped me through my breakdown and we talked often, one bipolar bear to another. And then one day I realised that, for the first time in fifty years, we were close.

I guess he realised, as we had to realise, that, out of the seven people who made up our household, only three of us remained; and the absence caused by my sister’s death would always cast a shadow over us. We were all we had left of the family we’d grown up with; the only ones who could remember, could understand. And we really needed each other.

I talk to my brother Keith every week now and we have commiserated as I have fought my battles with my failing career; and as he has fought his against his bouts of unemployment, his inadequate health insurance and his cancer. One night I told him I loved him. I think it was the first time.

“I love you too,” he said, also for the first time.

It was time for him to give up his secrets. Even though it was not quite James Bond.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

3 comments:

Baying, your blog is a work of genius! Warm! Funny! Poignant! Profoundly moving! I can't wait for the next installment to be posted!

I really mean that. ;)

- Penguin

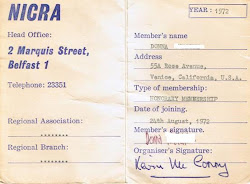

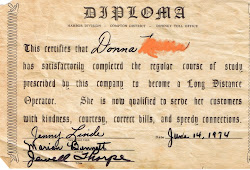

Hi Donna,

Christina asked me to read this particular blog. It was interesting to learn about more about your relationship with Keith. I especially like your story about the gate being closed. Christina asks me all the time about childhood memories and it's difficult for me to remember. It seems like those memories are pretty vivid in your mind. Oh yeah, I don't think I would want to stay in the seasons of Chicago either. I endured the end of winter and the middle of summer while I was there. I enjoyed your blog very much and I think it's great that you share these stories. It's always great to learn more about family. Tell everyone I said hello and take care.

Out of all your accomplishments I think your Mom would be most proud of your growing closeness to Keith.

Being verbal people we tend to think that because other people don't speak about their feelings they must not have any.

Post a Comment