Mr and Mrs Anderson lived next door to us. They were childless, which made them pretty exotic. Particularly being Catholic, I simply didn't know any grown ups without kids who weren't nuns, priests (little did I know!) or my great Aunt Irene who rarely talked to us but talked to herself constantly. (I was always told it was because she'd had polio as a child, but suspected she was just rather mad; a thread, I would discover, that was woven into the fabric of both my mother's and my father's families. What hope did I have? I used to think. As it turned out, none whatsovever.)

Mr and Mrs Anderson did not find children endearing. They didn't smile when we blurted out something undiplomatic, or broke something in our overexcitement, or screamed just to see how loud we could do it. The only thing that Mr Anderson loved, as far as I could tell, was his dichondra lawn.

A dichondra lawn was, as everyone knew, almost impossible to achieve. But Mr Anderson was no average gardener. He had created in his front yard domain a rich carpet of velvety green made up of tiny clover-like blades of something that was surely not grass. You couldn't call it grass any more than you would call a sharp-finned shiny Cadillac a car. To keep it in perfect condition, he never even walked on it unless he was weeding, mulching, feeding or watering it; and even then only in his bare feet.

He scowled at our parched patchy front lawn and quietly cursed the weeds in it whose seeds blew onto his precious dichondra. Mr Anderson was constantly weeding his dichondra and keeping a jaundiced eye on the comings and goings of the band of renegades who were the children of his next door neighbour, a woman who wasn't even respectable enough to have a husband. Although he complained to my mother and grandmother on a number of occasions about our cutting across his front yard, he failed in his attempts to get us to act like anything but the kids we were. And so he erected a fence made of a few short sticks with string run between them, to make it plain that trampling his dichondra was not to be tolerated.

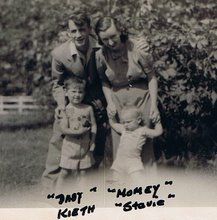

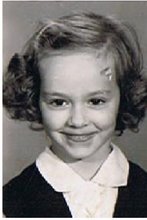

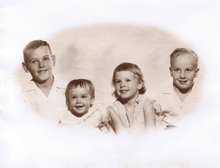

We didn't take nearly as much notice of Mr Anderson as he took of us. I was five and my sister seven at the time; and we reasoned that Mr Anderson simply refused to appreciate that my brothers were not beholden to the kind of rules mere mortals must adhere to. Because they were geniuses.

My brother Steve was some kind of Einstein and I was in awe of him. He was an inventor of rare talent in my view. Having watched a fairground ride astutely, he attempted to create a ride at home that I could sit on and be carried round and round as long as I wanted without paying for a ticket. Unfortunately, the only motor he had to power it was from the Erector set he got for Christmas. But any genius, surely, has to experiment with prototypes first! When he was given a small tape recorder, it was his pride and joy and he couldn't wait to find out how it worked. I was profoundly impressed by the deftness with which he took it apart and removed it innards to examine them; and just because he then couldn't put it back together again, it didn't make his experiment any less impressive. He had an intellectutal curiousity that I thought was breathtaking. Once he wanted to know how it felt to be locked in the trunk of a car, so he went inside the trunk of our battered old Plymouth, Brutus, and had us close it and then open it again to let him out. He said it was thrilling and each of us four had to try it then. Wow. Pitch darkness like I'd never known! We continued to do this over and over until Steve suggested we all get in at once and see what it was like. So we enthusiastically climbed in and slammed the trunk closed. One minor hitch was that there was now no one outside to let us out again. I started to yell for help but my sister Nancy, always practical and having seen a lot of movies on this theme, told us we must save our oxygen. I tried to hold my breath. But my brothers found that the parcel shelf behind the back seat was accessible from the trunk and pushed through it to save the day! I was so proud of them, but they had great humility, I thought, because they told me that on no account should I tell Mom.

And Steve did have another very useful and unique talent. It involved going to the annual church fair and standing at a stall where there was an uprght homemade wheel with numbers on it. People were encouraged to place bets on what number it might land on when it was spun, so it was a lot like the poor man's roulette. (And at a church fair? Was gambling not on of the Seven Deadly Sins? Maybe not.) The prizes were bags of groceries, donated, as were all the prizes, by parishioners. Now my brother knew than no homemade wheel could be perfectly balanced. So if he observed it long enough, he figured he could make a fairly accurate prediction of the most likely numbers to come up. After watching for a very long time, arousing the unease of the volunteers manning the stall, my brother took out a roll of dimes and started to bet. He invariably came home with bag after bag of groceries until the Church stepped in and made him stop betting. My mother was embarrassed by his cunning, but very pleased to have the groceries.

There was a woodpile in the backyard that I think was there from before we moved in. I never went near it because I was convinced there were black widow spiders in it, which there probably was. My brothers thought some good use must be made of it.

Roller-skating was very popular then. But it wasn't like roller blading. The skates were metal, with four wheels, one in each corner, and designed to attach to your shoes. You used a roller skate key to open them, put them on, and the tighten them to fit your foot. We all had roller skates, but there are only so many times you can fall down on the hard concrete sidewalk or run into a lamppost before the thrill is gone. My brothers Steve and Keith had a brilliant idea about what to do with the unwanted skates. They would build a car for us to ride around in from the old wood and the wheels from the roller skates.

This, I thought, was the most creative and ingenious plan they had come up with yet! Imagine cruising around the sidewalks in our homemade car!

They set about making it, fearless of the black widows that I knew were in that woodpile, using hammers and nails and looking incredibly impressive as their design took shape. In the end it was huge! The four of us could sit in it, two in the front and two in the back! There was only the wheels to put on now and we'd be cruising. There was a minor hitch though. The car was so spectacularly heavy and the roller skate wheels so pitifully small that our beautiful car would not move an inch. My brothers were undeterred by this small setback. The wheels were taken off the car and it was left in the backyard and now called a "clubhouse".

They now had an alternate plan. If the car was too heavy they would need to make something lighter. There was an old wooden door on the woodpile and genius took its course. They attached the roller skate wheels to the door and a small rope which they would use to steer it. I looked at it sceptically.

"That's not a car!" I said.

"Of course not," Keith said, "It's something much better. It's a heelykididdlywatt."

Now I had never heardof a heelykididdlywatt before, and I suspect my brother made this up on the spot, but it did look promising. Much lighter than the car.

The street we lived on was on a hill, so we dragged our heelykididdlywatt up to the top and prepared to take it for its maiden run. The door was big enough to accommodate all four of us and my brother Keith sat in the "driver's seat" in front and held the steering rope, and Steve, Nancy and I sccoted up behind him. I looked around to see who might be watching us because I was sure they would be very jealous when they saw our beautiful heelykididdlywatt careening down the sidewalk.

We set off from the top of the hill and I was delighted to discover that, this time, the vehicle they'd created was not too heavy and we gathered speed at a terrific rate as Keith steered us down the hill! The thrill was unbelievable and I screamed at the top of my voice with excitement. What an invention! Surely we could market this and become rich!

Now unfortunately, despite the steering rope, the heelykididdlywatt had no axle. So the concept of actually steering it, as in making it go the way you wanted it to, was really not a part of its design. So when the thing started to veer to the right, there was really no way to steer it back. And, also unfortunately, the heelykididdlywatt had no brakes. My brothers had been thinking more about how to get it going than how to stop it.

As Keith struggled for control, it became obvious that the only thing to do was to bail out! But we were going so fast! And what if we ended up in the street and got run over by a car? The door on wheels finally veered off the sidewalk and hit something soft and then tipped us all out violently on the ground, but at least in one piece.

As I lay there on the ground, the first thing I saw was dichondra.

When we got up, shaken, we saw the deep ruts the roller skate wheels had driven into the ground, churning up carefully mulched soil and pulling those little clover like blades of Cadillac grass up by the roots; and the squashed dichondra where we had all been pitched out. Mr Anderson had run out of his front door but, by instinct, still didn't tread on his dichondra, choosing to shout angrily and with tears forming in his eyes.

"What have you done?" he shouted, "What is that?"

Steve brushed the soil and bits of dichondra from his patched jeans.

"It's our heelykididdlywatt!" he said proudly, "What do you think?"