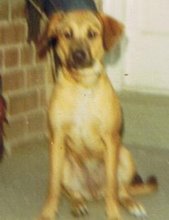

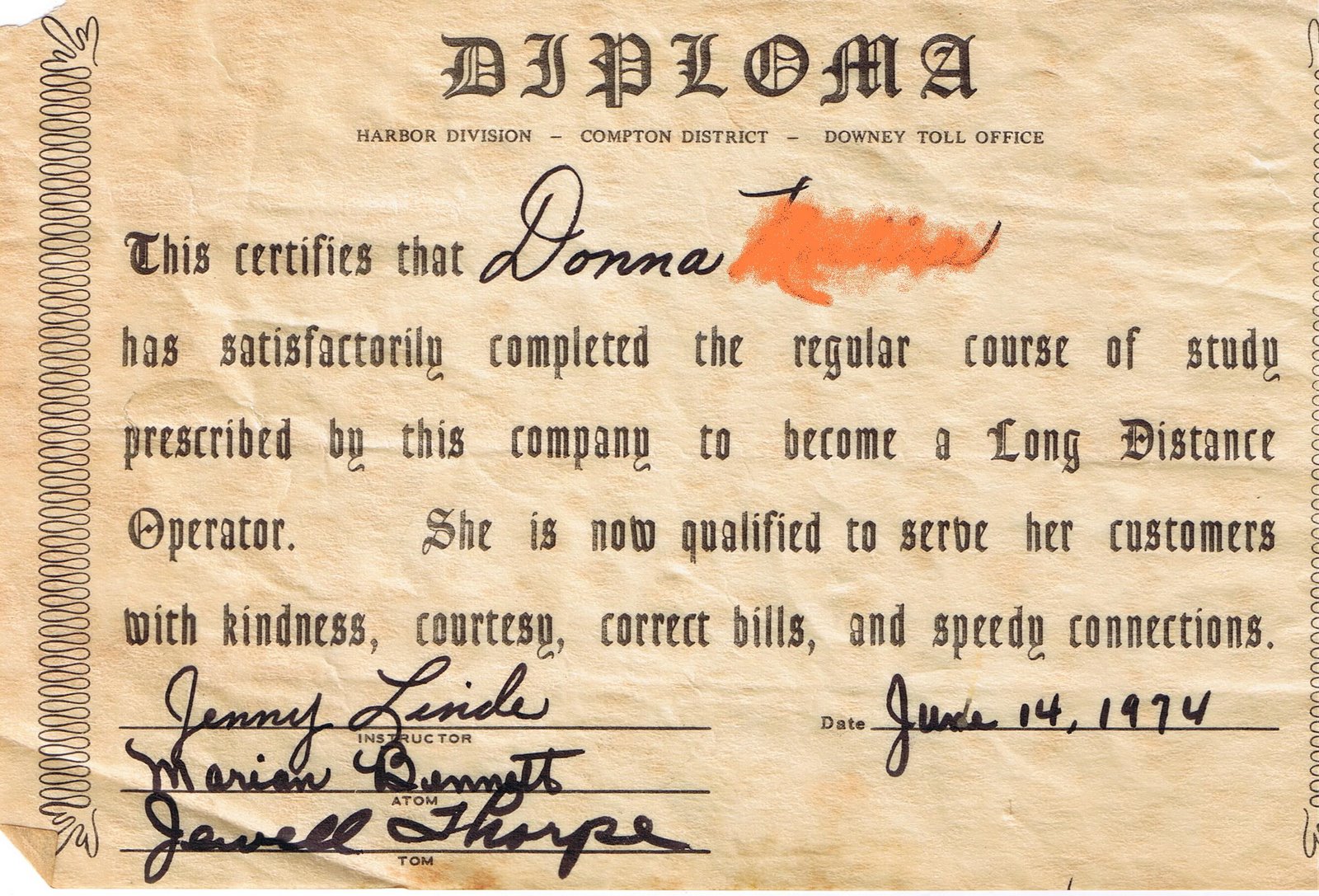

When I was twenty years old, I decided to kill myself. I had left college and was working as a telephone operator. I had been chucked out of the little house in Venice that I had grown to love by my new landlord who’d doubled the rent. I had no friends. Gone were the smart, passionate intellectual-types I had known during my years at UCLA. Instead I was surrounded by women who planned Dime-a-Dip Days to raise funds for the Lone Wolf Colony, a rest home for burned-out telephone operators. I would wake up in an empty apartment. I would come home to an empty apartment – unless you counted my dog Gimbol, who was very devoted but not much good at conversation. (It’s difficult when you’ve only got a tail.) I was alone, isolated and desperately lonely. And I had come to realise that my plans to become a writer had been sad delusions. So it seemed to me that, in the circumstances, I was making a totally rational choice. In fact, I was as mad as a box of frogs.

I had a headshrinker at the time, the latest of many. His name was Greg. He was young and had the intense look of someone trying very hard to be taken seriously. He dressed with a studied casualness that fooled no one. I had found him through a charity offering free psychotherapy and my case had been handed to him.

He was one of those shrinks who always talked as though he knew you so much better than you knew yourself. Most shrinks are like that in my experience. And I had had a lot of them.

First there had been Eddie from the Long Beach Free Clinic. He was a very short black guy (anyone who can look me straight in the eye while standing is short!) who had an earring and wore moccasins. (It was 1969, what can I say?) I spent a lot of time looking at his moccasins because, when you’re depressed you look at the floor a lot. I guess he knew this and wanted to provide his clients with something interesting to look at. He would, however, look me in the eye every time I left his office and tell me he cared about me, and ask me if I believed him. I always said I did, but I what I really thought was, “Why should I care whether you care? You are a complete stranger for God’s sake!” But I think it was just something they teach you to do in Shrink School.

There were also a couple of useless ones in there who I barely remember; and then there were Alan and Dave, the trainee shrinks that ran my therapy group while their professor looked on from behind the one-way glass. I once got so upset at a therapy session that I ran out (I was such a drama queen back then!) and was pursued by the Professor-From-Behind-the-Glass until he caught me. Wheeling me around he realised I was not the group member he thought he’d been chasing, apologised and sent me on my way. I was a bit miffed. Why didn’t I deserve hot pursuit?

Then there was Dr. Whatsisname from the Neuro-Psychiatric Institute at UCLA who I was sent to when I was first thought to be suicidal. He was about fifty, wore a suit and didn’t look at you when he spoke. The lights in his office were dimmed and he really did have one of those psychiatrist’s couches in his office! (I thought those only existed in the movies!) He invited me to lie on the couch, but my mother had always told me never to lie on couches when invited to by a men in a dimly lit rooms. So I declined. I sat on a chair, made him turn the light on, and talked to him for about ten minutes before I’d decided I’d had enough. I got up and left; at which point he chased me up some stairs. (I obviously wasn’t going to rest until someone chased me for myself, not someone else!) Realising that I might get committed or something, I convinced him I was actually fine. Because all these shrinks all had one thing in common. I could make them think whatever I wanted them to think.

Being depressed means having an entirely dysfunctional view of the world, and challenging it can be tiresome and even distressing – so best avoided. So if I felt weak and wanted to be thought stoic, I would casually drop colourful accounts of childhood trauma into my sessions, and then minimise them. They could never resist admiring my fortitude. If I wanted to paint myself in a good light, I would say why I totally understood why someone had been horrible to me. They could never resist taking my side. If I didn’t want to discuss something painful, I would change the subject with a story of real anguish that was too good not to follow up. I was very good at this. We all want to be liked. And shrinks prefer to like their patients. So it was a Win-Win situation. The only drawback was that my dysfunctional view of the world remained entirely intact.

Don’t let anyone tell you psychotherapy is a science. It is an art form. There are as many good shrinks as good artists. (I have had two good shrinks and they know who they are. Hello Kit! Hello Alan!) And Greg was no artist -- more like the Sunday dabbler painting bad oil landscapes and trying to sell them (unsuccessfully) at craft fairs.

He was a nice enough guy though. I was in a pretty bad way and he had given me the number of his answering service (this was in the olden days, before answering machines and cellphones) for when I was in crisis. He even took me out to a pizza place one night after a therapy session. Which, when you think about it, was a pretty outrageous thing for a shrink to do. I mean he could have at least taken me to a Denny’s!

He worked with an actual doctor-type psychiatrist who prescribed me a tricyclic antidepressant called Tofranil. Greg held the bottle out to me solemnly and said, “I am handing you something that has the potential to help you feel a lot better.” He paused. “But I am also handing you a loaded gun.” Tricyclics in overdose, he told me, can kill.

Now I reckon I really didn’t need to know that. He could have said, I am also handing you a bag of snails. Or a squishy banana. Or an out of tune harmonica. But he didn’t. He told me he was handing me a loaded gun. And me a pacifist and everything.

I didn’t come to the decision to kill myself all at once. I played with it. Wondered what it would be like to be dead. (Which was a pretty bizarre thought really!) Imagined the pathetic little band that would turn up for my funeral. I played with the idea on many empty nights when watching TV or playing Solitaire had lost its appeal. It flitted around me like a butterfly, lit for a short while, then fluttered on. Until one night I found myself thinking, “I could really do this.”

From then on I felt very calm. As if I was organising my own death was no different from organising a trip to Disney World or a car loan at the credit union. Except, of course, that I had a loaded gun.

I kind of had Marilyn Monroe in mind when the night came for me to do it. I arranged the Tofranil tablets I’d hoarded on the dining table, along with other promising medications including the codeine I’d been prescribed for menstrual cramps; and I swallowed every one. I thought it might be nice to be discovered (Monroe like) lying naked and oddly seductive on my bed in the early morning light.

But on my way to my nude, seductive sleep, it occurred to me that I had forgotten to leave a suicide note. I was by then too groggy to be able to do this properly (I had my writer’s vanity after all), so I called Greg up through his answering service to dictate one. I suppose I was hoping he was going to talk me out of the whole thing; and I suppose he was hoping to talk me out of it too. But, to keep my options open, I told him I was calling from a public telephone.

Now, I’ve never known how shrinks can stand talking to depressed people all the time. We do go on and on and on and on about the utter hopelessness of our situation: “My life is crap. Please don’t ask me to believe it will ever be anything else. Please don’t ask me to do anything about it. Please don’t try to cheer me up.” If I were a shrink, I would eventually snap, slap someone on the side of the head and say, “Get a grip, for God’s sake!!!” So I guess it’s good I’m not a shrink. They are all saints. Often incompetent saints, but saints.

So finally, being a Sunday painter of dubious talent but, fatally, thinking he was Picasso, Greg decided to try reverse psychology on me. Any parent can tell you this trick doesn’t even work on recalcitrant toddlers. Try it and see. Tell a fussy three-year-old, “No you can’t have this broccoli! It’s all mine!” and you will just end up eating a lot of broccoli while the child looks contemptuously on. But Greg obviously thought it was a good idea.

“Okay,” he said, “You’ve convinced me! You’re worthless. I think you should kill yourself! I thought you were a really good person, but now I see that you’re not. So why not? Do it!” He had given me the murder weapon and he had given me the motive. Agatha Christie eat your heart out. I hung up.

Oddly, I suddenly felt embarrassed about the whole thing. What if he sounded the alarm and someone ended up storming in here and found me conscious and naked and scrabbling for my ratty robe? That would be mortifying! So I went into my walk-in closet, concealed myself by rolling up into a carpet that was stored there. And fell into a sleepy haze.

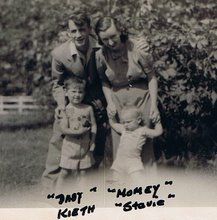

Well of course Greg did sound the alarm. He called my mother who called my sister who broke down the back door and found…an empty apartment. Except for my dog. My sister and her husband looked everywhere. I could hear them looking. They didn’t find me. Then I heard my dog whining at the door of the walk-in closet. My sister opened the door, discovered me there and called an ambulance. “Damn dog!” I thought. “What a time for her to play Lassie!”

What happened next is kind of a blur. It involved an ambulance; a guy engaging me in some spurious conversation as we sped to the hospital that involved him being hugely interested in the fact that I had once been a Candy-Striper (hospital volunteer), which I thought was as ludicrous as it was annoying when all I wanted to do was go to sleep; an emergency room; my family turning up; me throwing up a lot; and finally being transferred to another hospital where I distinguished myself by shitting all over the bed twice during the night. Marilyn Monroe this wasn’t.

The next day I came round very, very slowly. My first thought was, “Please, God, don’t let me be in a loony bin.” I opened my eyes, just a touch, to see where I was. There were no bars on the window. I was okay. Phew. A nurse came with a pitcher and a glass, and told me I had to drink lots and lots of water. I sat up in bed groggily and was immediately greeted by a smiling, if ever-so-slightly-bonkers, woman who introduced herself as Debbie.

“Hi!” she said cheerfully, “I tried to kill myself too! I took eighty-three sleeping tablets! I mean, was I serious or what?” And it was then that I noticed. The windows were key-operated.

I knew I had to get out of there and I figured my best bet was to act like a normal person and plead accidental overdose. I had to go for a pee (unsurprising with drinking all that water). So I got out of bed like a normal person. I sauntered down the hall like a normal person. I went through a door marked ‘Women’ like a normal person, had my pee and then washed my hands and went back to bed like a normal person. This was going well.

When I needed another pee about five minutes later (hey, it was a lot of water!), I got up like a normal person. I sauntered down the hall like a normal person. I passed a door marked ‘Men’ like a normal person. And I carried on walking down the hall until I came to the end of it. I must have missed the door.

So I walked back up the hall like a normal person. I passed a door marked ‘Men’ like a normal person. And ended up back at my bed. How could I have missed the door twice? Damn.

About ten minutes later (and really desperate for a pee by nnow) I was still walking up and down the hall looking for the Womens’ Room and hoping no one had noticed me. But Debbie had.

“Why are you walking up and down like that?” she nearly shrieked. “You must be crazy! Crazy, crazy, crazy!” she continued, just in case anyone on the ward, or indeed the entire floor, had missed it.

When I finally told her I couldn’t find the bathroom, she laughed her head off and led me to the door marked ‘Men’. “But that’s the Men’s Room,” I protested. Debbie turned the ‘Men’ sign over. On the other side was the word ‘Women’.

“It ain’t now,” she said. It was a unisex bathroom.

I was eventually able to sign myself out Against Medical Advice, and went to stay with my mother while my sister went through the medicine cabinet and threw away anything that she thought could possibly be used for another suicide attempt. She was very thorough. Why she thought I might try to do myself in with ear drops, though, is anyone’s guess.

My mother was particularly concerned about how a psychiatric admission was going to look on my work record, but I managed to convince Downey Toll that I was suffering from Nervous Exhaustion (which everyone knows translates as Mad As A Box of Frogs anyway); and I even got myself signed up for several days of rest and recuperation at the Lone Wolf Colony out in the California desert, which made me very sorry I hadn’t contributed more to those Dime-a-Dip Days the other operators had organised.

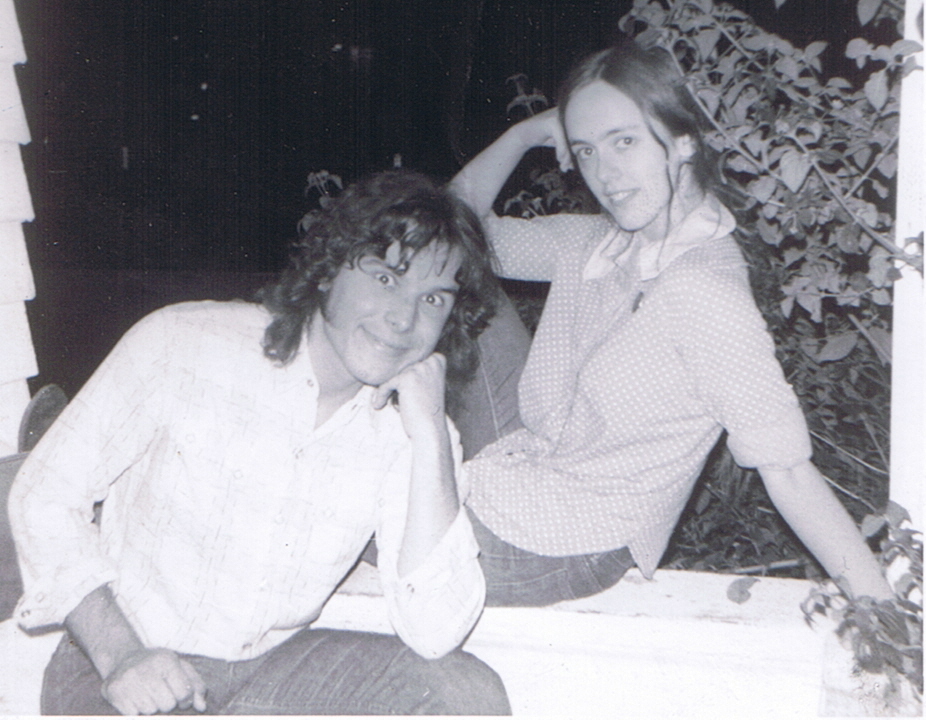

My stay at the Lone Wolf excited a certain amount of curiosity when I went back to work, and everyone wanted me to tell them about it. Inexplicably, I found myself making friends. Like Joan, who riveted planes during World War II and Emma, a teenager who got pregnant the very first time she reluctantly had sex with her boyfriend, and Pat who was a single mom and desperate to find a way to go to college (which she eventually did), and Sherry who became my best friend over countless drunken evenings (when we decided that alcoholics were people who drank alone so as long as we drank with each other we weren’t alcoholics) spent talking about how useless men were -- except for the ones who were good at sex. And I wondered why I had never noticed what warm, funny and extraordinary people these were before?

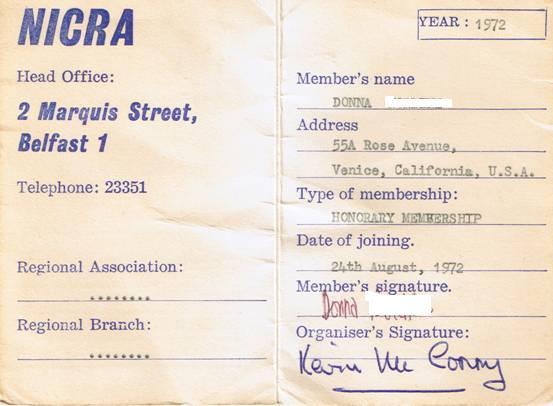

A year later my yearning to become a writer could be contained no longer. My high school drama teacher, I remembered, had once said in passing that London was the best place in the world for theatre. Taking his word for it, having done no research whatsoever, not even about the climate there, I decided to quit my job, give up my apartment, give away all my furniture, board my dog with my mother, and move to London where, I felt certain my prodigious talent would be sure to be recognised and feted! I was, of course, barking mad at the time, but that is how I ended up living in Britain.

If I had died that night back in 1974 and not been thwarted by a dog who’d watched too many episodes of “Lassie”, there are so many things I would not have been around to suffer: the relentless rejection of my work, being left by someone I desperately loved for another woman, watching my sister deteriorate and die at the age of thirty-six; and I would have missed all those years of longing for a child as my periods arrived with cruel predictability, the collapse of my career not once, not twice, but three times, the sting of betrayal and loss, and the terrible, desperate and ever-returning loneliness.

And yet. And yet. I would never have known what it was like to spend long summer days with a new love, never getting out of bed; never known what it was like to snatch that first success from a sea of failure, or the thrill of watching actors saying words I wrote or seeing my picture, however fleetingly, in a newspaper; never have had friends come into my life from unexpected places, made Thanksgiving dinner for twenty people who didn’t even know what Thanksgiving was, never had a chance to be a shoulder to cry on and to be able to say, from the very depth of my soul, that I understood; and I would never have known what it was like to raise my beautiful, beautiful son, to love him unconditionally, and to know that I would cheerfully throw myself in front of a two-ton truck to save his life. Now that would be something worth dying for.

When I left Downey Toll for the last time, en route to who-knows-what in London, the operators threw me a party at Shakey’s Pizza Parlour and bought me a sweater as a going-away present because they thought England would be pretty cold. I realised that something magical and totally unexpected had happened. I belonged. And suddenly, I didn’t know whether I was really doing the right thing to leave.

Joan, who had always been a mother figure to the younger operators, had always envied the chances the new generation of women had; envied that we could do things, be things that would have seemed far-fetched in her day.

“You go out there and you do it, godammit!” she hissed at me. “If you stay here now, you’ll never leave. It sucks you in! Don’t let it suck you in! Just take your life and your hopes and go!”

And so I did. Joan was right. Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is to hope. And to choose to live.

1 comment:

Oh mygosh thank you. You may never know how many people need this today, any day. And then again, I guess you do....

Post a Comment