My father’s parents were Swedish, which made him Swedish and that makes me one-half Swedish I guess; despite the fact that I am as far as it is possible to be from being blonde, blue-eyed, tall, leggy, busty or any of the other enviable attributes associated with that race as it is possible to be. My maternal grandmother had two Irish parents which made her Irish, my mother half Irish, and me one-quarter Irish.

I take after the short, small-breasted Irish side. God sure has a sense of humour.

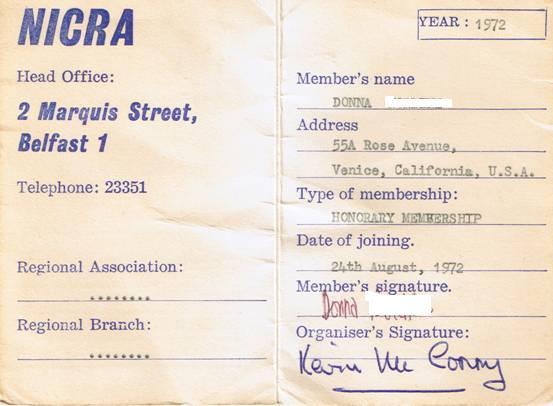

Like most Americans, I was quite interested in my hyphen. I think we tend to be Swedish-Americans or Irish-Americans or Italian-Americans or Afro-Americans because ours is such a young country by world standards (if you’re Greek your race goes back thousands of years!). We need a bit of help knowing exactly who we are. My family identified with being Irish-American.

One day, while paging through my mother’s Catholic weekly newspaper, looking up the Catholic Legion of Decency movie ratings for a laugh (“Never on a Sunday” was a Condemned Film. So that’s another Mortal Sin I chalked up!), I found an advertisement for a two week summer course in traditional Irish music at University College Cork in Ireland.

My brother had just returned from backpacking around Europe, and had been entertaining us with stories of panhandling in Spain, drinking Mateus in Portugal, and a riding a motorcycle with a sidecar through the Pyrenees. I desperately wanted to go and have a similar adventure before I settled down in a couple of years with my fiancé, who was due back from Vietnam that summer. The problem was that I was then sixteen years old and my mother was never going to let me. (She wouldn’t have let me get engaged either, but she didn’t know about that…)

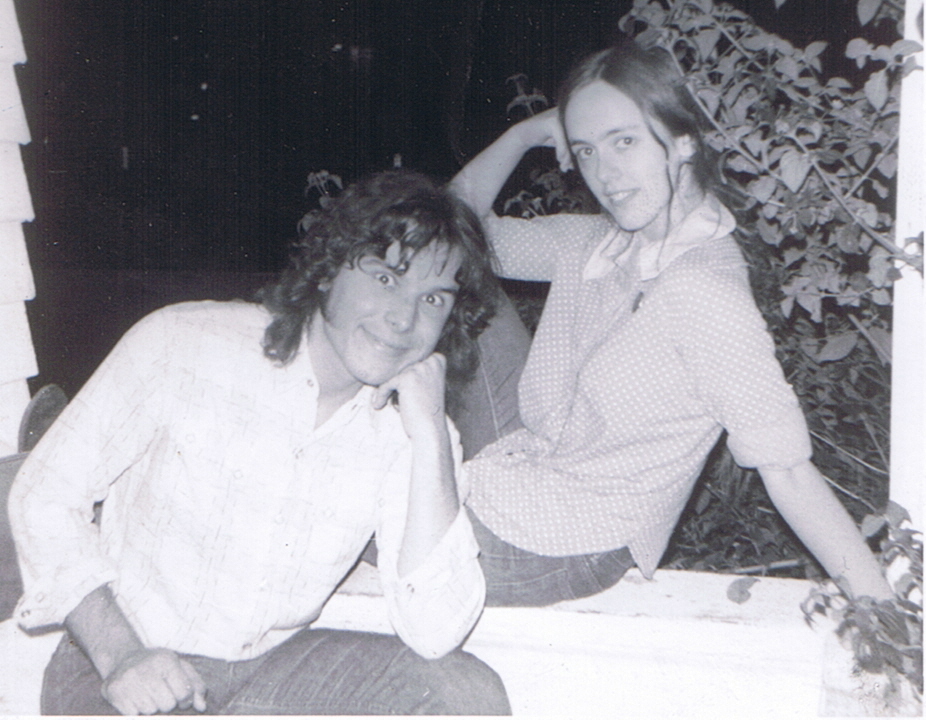

I instantly realised that this advertisement was my Big Chance. Surely she couldn’t refuse me the opportunity to go the Old Country on a traditional Irish music course advertised in a Catholic newspaper with my mature and responsible eighteen year old sister. So the first thing I had to do was persuade my mature and responsible eighteen year old sister..

We had just been sent eight hundred dollars from my father’s estate, which was a lot of money then, and I challenged my sister to think of a better way to spend it. It was important not to let her think too long about that, and I didn’t, so she caved in immediately and so did my Mom.

Now I am the kind of person you should never give an inch to, because I will always take the proverbial mile. By the time my mother knew what was happening, we had discovered the existence of Youth Hostels and had decided to spend seven weeks touring around Ireland, England and Scotland, and had even planned a trip to Paris for Bastille Day. (When I say “planned”, I use the term loosely. We arrived on the biggest day of the Paris Tourist Calendar without reservations and ended up sleeping in a park where we had our Polaroid camera stolen.) She didn’t put her foot down until we started talking about renting motorbikes! (She might not have been quite so adamantly against this had she realised we were going to hitch-hike instead.)

Word spread through school that I was going to Europe for the summer. I’d never had so much cachet at school. And when my eccentric high school history teacher, Mr. Drake, heard it, he insisted that we absolutely had to drop in on his Uncle Michael who had a small farm in Connemara. This was turning into quite an adventure and we hadn’t even left yet! Mr. Drake gave us a map and I asked for his uncle’s phone number. He smiled.

“Oh, they don’t have phones there.”

As a teenager who was never off the phone, the idea that there could be a place in the universe that didn’t have phones was beyond my imagination. So when we landed at Shannon Airport and realised that Connemara was only a short distance away, we had no way of warning him we were coming. But we were coming.

We took the airport bus to Galway and then searched for a bus that would take us to Michael O’Sullivan’s house. We discovered two things: no buses went there, and that the bus that went near it only ran twice a day. So we started to hitch-hike.

By the time we got our last ride (from a tractor pulling hay) we were on a small dirt road with high hedges on either side. The driver dropped us off and pointed the way to Michael O’Sullivan’s house which he said was about a mile away. Of course it was a whole lot further than that. In Ireland they tell you something is a mile away when it's five, two when it's ten, because they don’t want you to get discouraged about your journey.

After a couple miles, we encountered a man of about sixty who was striding purposefully down the lane in the opposite direction, his Wellingtons splattered knee high with mud.

“We’re looking for Michael O’Sullivan,” my sister said. The man started and looked us up and down.

“I’m Michael O’Sullivan!” he said, “Who are you?”

As soon as he realised we were friends of his nephew, we were welcomed with open arms. He insisted that we stay with him and his wife, Ann, and that he would lay on the best he had to offer.

They lived in a remote two room cottage with only the most basic furnishings and a peat fire for heat. Dinner was lunchmeats, bread and butter, and tea. There was no television, only a small radio. When I asked where “the bathroom” was, I was shown to a door – that led outside – and Ann handed me some toilet paper. There was no running water. And yet the hospitality shown to their unexpected guests was warm and almost over-generous. A precious tin of biscuits, obviously given as a Christmas present six months before, was opened in our honour. I found it hard to believe that in 1970, in what was supposed to be a first world county, there could be this kind of poverty.

By the time we set off for the course in Cork, we had hitched to Dublin, staying in a hay barn on the way. The farmer had asked repeatedly, “You don’t smoke do you? You don’t smoke, right?”, before bringing us a hot supper. We had seen the O’Connell Street Post Office where the bullet holes from the Easter Rising remained in the plaster, and I thought it odd that no one had got round to fixing them yet. The rising had been in 1916 after all. We got a lift to Cork from a crazed salesman who drove ninety miles an hour on narrow roads with hedgerows on either side, and stopped for a pie and two pints of Guinness on the way.

Our accommodation for the course, at St. Kilda’s Guest House on Cork’s Western Road, was luxurious by comparison to the very wet camping we had been doing. We got to eat a huge cooked breakfast every morning, an afternoon tea of sandwiches, tea and scones; and a huge dinner in the evening. At lunchtime, we went to a hotel in the centre of Cork and were served by the same loquacious waiter every day, who drew us into conversation about the wonderful Common Market Ireland had just joined (we hadn’t a clue, having only just heard about it), his American relatives (everyone has them) and our bizarre habit of ordering custard with nothing for dessert. (Well, we liked custard!) All included in the price of the course. What a deal!

Two other people on the course were staying at St. Kilda’s. There was a middle-aged blind man who talked like W.C Fields and sat in the front of the class, pontificating about Irish traditional music in a way that suggested he knew more about the subject than the esteemed teachers. (This drove at least one of them mad. I thought at one point he was going to say, “Do you want to get up and do this?”)

His carer and sidekick was a awkward, weedy-looking guy who knew nothing about Irish traditional music, but told us he was famous throughout Minnesota for being able to do a perfect imitation of a Hawaiian guitar. He told us it was indistinguishable from an actual Hawaiian guitar if you closed your eyes, and demonstrated on a number of occasions. If only I had been able to close my ears as well. I could only guess that not a lot went on in his part of Minnesota.

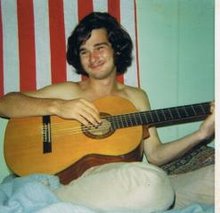

What my sister and I discovered when we took the music course was that we had an entirely different idea of what folk music was than they did. Their idea was music played on tin whistles and uilleann pipes to the beat of a skin drum called a bodhran , sung in an incomprehensible ancient language called Irish. Our idea was anything you could play on an acoustic guitar. When we were asked by the teachers to sing an American folk song for the group, we got up and sang “Leaving on a Jet Plane” from a Peter, Paul and Mary album. It did not get the rapturous reception I had hoped for.

The first sociology class I ever took taught me that, “In some ways we are all alike, and in some ways we are only like others in our group, and in some ways we are only like ourselves.”

It took me a while to understand the middle part of that; to realise that, between what we, all of us, are, and what we uniquely are, is culture. America is such a huge country. We can travel three thousand miles and still see American flags flying on buildings, still buy the same foods, still shop at the same stores and complain about the same government.

Until I went to Ireland that summer, I had no more understanding of the cultures of the world than can be gleaned from the “Small World” ride at Disneyland.

Despite its poverty, I discovered, Ireland had a rich literary and musical heritage. There was a cultural revival going on in those days. The composer Sean O Riada was writing music for orchestras of traditional Irish instruments, The Chieftains were touring traditional music around the world. People were speaking Irish, the language that had been nearly lost by centuries of English occupation.

So my sister and I learned songs in Irish, and did some ceilidh dancing, and listened to the uilleann pipes, and learned a bit of Irish from a book that should have been retired decades before. (Did you know that “Ta capal an tsagairt bacach” means “The horse of the priest is lame? Just a handy phrase in case you ever need it! (And, if you’re an Irish speaker and I’ve got the spelling wrong, please leave a comment correcting me.)

On the day of the final concert of the course, my sister and I were on our way to get some batteries so we could record it on our cheap and nasty cassette recorder. We ran into the composer Sean O Riada, one of our lecturers, who insisted on taking us to the pub for a pint. I had never had a drink before so I asked my sister how she thought I could politely refuse. She told me to tell him I was a Quaker.

“What’ll you have?” he asked us as we entered the pub.

“The thing is,” I said, “I’m a Quaker.”

“Alright, you Quaker, “ he shot back, “What’ll you have?”

I tried to explain. “See, the thing about being a Quaker…” but he wasn’t listening.

“Okay!” he said, “Pint of Guinness!”

A few minutes later he returned with the largest glass I’d ever seen full of a completely black substance with a cream-coloured top.

“Slainte mhaith!” he said, raising his glass. I smiled nervously, raised mine back and sipped. It was awful! Really bitter! Who could drink this stuff, I thought? But I drank it anyway and by the time the glass was empty I thought it tasted pretty good. The detail of the rest of the afternoon is a bit fuzzy.

That night Sean O Riada came up to me after the concert.

“Well?” he asked, “Are you drunk or are you sober?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted.

“If you don’t know,” he told me, “then you’re drunk.”

My course in Irish Culture was now complete.

We flew back to California at the end of the summer. My fiancé came back from Vietnam. He had changed a lot and the engagement didn’t survive the walk to the airport parking lot.

But I’d changed too I guess. My horizons had shifted. There was a whole big world out there beyond the green-painted asphalt of Bellflower, I’d discovered, and I wanted to explore it.

A few months after I got back from Ireland, a friend brought me a bottle of Guinness that he’d bought at a store selling exotic beers. It was a lovely thought. But it didn’t taste the same as it had in Ireland.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.

3 comments:

Hi Baying,

have found my way here, haven't read everything yet, but this is just a wonderful blog;

warm wishes hedge

How marvellous about Sean O'Riada. He composed, around traditional airs, the music for the famous film Mise Eire (I am Ireland), primarily Roisin Dubh (representing Ireland, as in Mangan's "My Dark Rosaleen") and the haunting Mna na h'Eireann (Women of Ireland), later played by the Chieftains on the soundtrack of Barry Lyndon.

Post a Comment