When I came to Belfast in the summer of 1972 I told my mother I was going to Dublin. I wrote quite involved works of fiction about my exploits there, put them in envelopes addressed to her, and then sent them on to a friend in Dublin who sent them on to my mother who was reassured by the Dublin postmark. My mother always underestimated just how sneaky and underhand I was. Which, in this case, was just as well.

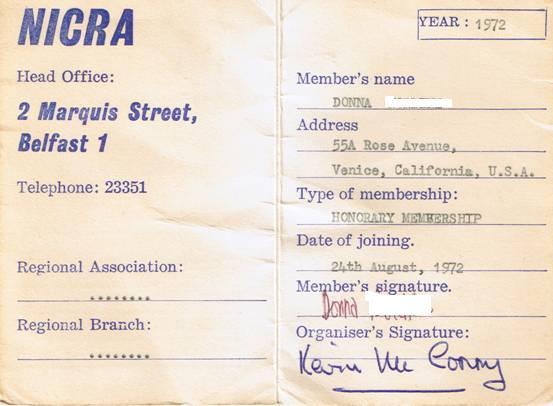

1972, though no one knew it yet, was to be the bloodiest year of the conflict in Northern Ireland. It’s hard to remember, when we look back, that it had started with a civil rights movement. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) had modelled itself on the struggle by black Americans for civil rights in the 1960s, just as surely as the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, had modelled itself on the government of America’s Deep South. Catholics were discriminated against in employment and housing, and were disenfranchised by clever gerrymandering and by outright corruption. By 1972, however, the peaceful campaign for civil rights was degenerating into civil was.

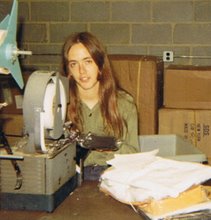

Though it was a campaign that was rapidly being overtaken by events, I can at least say I played my part in it. I filed things. I proofread stuff. I did a lot of typing. (No word processors back then, just Tippex. And, with my terrible typing, my copy often looked a bit like Jackson Pollack in white. I would have been fired me had I not been working for free.)

I found a place to stay for the summer in a student house on Stranmillis Road near Queen University . It was only a fairly pleasant twenty-five minute walk to the NICRA office in the city centre, which passed the heavily fortified Europa Hotel. Until Sarajevo, it was the most bombed hotel in Europe.

NICRA were then heavily involved in the anti-internment campaign, in protesting against the Widgery Report about Bloody Sunday which they considered a whitewash (which, most of us would now agree, it was) and in following up complaints of ill treatment by British Army soldiers. These incidents had become all too frequent since the days when the British Army had been first been deployed there to stop sectarian attacks on the Nationalist population. In 1969 they had been welcomed with cups of tea by the besieged and grateful residents. Now “No Tea for Toy Soldiers” was graffitied onto crumbling walls all over the city. Battle lines had been drawn.

So many complaints were now flooding in about the army’s behaviour that NICRA was often overwhelmed. In light of this, they took the rash decision to take me off typing duties (I think they must have got exasperated with all those layers of Tippex) and sent me out “in the field” to find cases suitable for a publication they were preparing o=on abuses by the army.

My first assignment was in the bleak ghetto of Andersonstown where I was sent to interview a woman whose husband was “on the run” (wanted by the army). The army had come in the early hours of that morning to search her house for guns.

By the look of it, they had been very thorough. The house looked like it was in the early stages of industrial demolition. The floorboards had been ripped up. The carpets were in shreds. The beds and all the soft furnishings had been slashed open and the stuffing pulled out. The bathroom basin and the toilet had been smashed to pieces. (I did wonder how guns could be concealed in a toilet bowl.) And in two of the rooms the walls had been pissed on. (Well, if there’s no toilet, what are they supposed to do, I guess.)

I was appalled of course and rushed back to the office to tell everyone what I had seen, sure that this was exactly the kind of thing that should go in their report. Kevim McCorry, the director of NICRA looked at me and shook his head.

“This is small stuff,” he told me. “This kind of thing happens every day here.” Every day, I thought? “The army will just say she did the damage herself to discredit the soldiers.” (How, I wondered, would they explain the piss up the wall though?) He shrugged and walked back into his office.

My next assignment was to interview a woman in Ballymurphy, an equally deprived and depressing ghetto.

When I got off the bus, I saw young kids playing in the street, as kids do just about everywhere I guess. They used to play football, but had to stop because they kept losing their ball every time it was accidentally kicked over the fence into the army barracks. The soldiers always refused to return the ball.

“You’re not satisfied with eight hundred years of plunder?” a ten-year old had once cried angrily. “You want a bloody ball as well?”

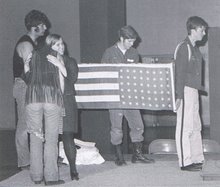

So, they had had to invent a new game called “Barricades”. They built a (rather pathetic) little “barricade” of sticks and rubbish and abandoned car parts, and then waited for a Saracen (an army armoured car) to come along and run over it with no trouble at all, and move on without stopping. The boys would then run out, rebuild it and wait for the next Saracen. During riots, they told me, they would dive around collecting rubber bullets, which they sold to their many journalist and cameraman customers for four pounds. It was very lucrative apparently.

Rubber bullets, which were then liberally used to control riots, were the shape and size of the average erect penis (according to Masters and Johnson) only quite a bit harder. (Apologies to any men reading this who are insulted by that; but I have never actually got bruises from being hit by an erect penis.) Because of their shape there were a lot of bawdy songs and jokes about women using them for “comfort” when their men were on the run or when they were under house arrest. But the damage they could do was no joke.

The stated use for rubber bullets was to disable rioters. They were intended to be shot at the legs of “ringleaders” so that they could be arrested. In practice it was a bit different.

I knocked on the door of a woman in her mid-sixties. She hobbled to the door to let me in, then hobbled back to the couch where she lay under a blanket as she spoke to me.

She was the archetypal cranky neighbour; the kind who complains about the noisy kids on the stairs, the people who forget to put the lids on their bins, the young guy upstairs with his heavy metal music and the half-deaf old dear next door with her radio and TV turned up too loud. So it was hardly surprising that, when she heard some soldiers in the street outside playing five-a-side football at two o-clock in the morning, she decided to come downstairs in her nightie and object to this very strenuously and in no uncertain terms. This football team, however, were well armed.

“Get away!” she had screamed at them, . “Get away from my door!” They had gathered around her, as annoyed as anyone ever is with a cranky neighbour.

“Get back in your fucking door, you Irish bastard!” said one of them, shoving her back through her doorway with his rubber bullet gun. The woman was incensed.

“Don’t you dare swear at me!” she admonished, advancing on him, her finger wagging furiously. And that was when he fired a rubber bullet into her gut at point blank range.

The woman lifted her nightie to show me her stomach. It was the largest bruise I had ever seen; spreading, in florid blacks, yellows and blues, right across her middle and from the bottom of her breastbone to under her navel.

When I came back to the NICRA office, Kevin McCorry told me I could write this one up. “They can’t say she did this one to herself!” I insisted.

“No,” he replied, “They’ll say she threatened them with a gun.” He had the weary air of someone who had seen all this before.

I spent the rest of the summer “in the field” for NICRA, while also doing all that invaluable typing, filing and proof-reading (at least they told me it was invaluable). I spent a lot of time in the Divis Flats area of the city, where I was always made welcome with cups of tea served in china cups with a plate of biscuits. And in every house I went to, or so it seemed to me, there was a hand carved miniature wooden harp proudly displayed in their knick-knack cupboard.

The harp is the symbol of Ireland, and Republican detainees in the infamous Long Kesh Internment Camp would churn these out for their friends and relatives to relieve the boredom of their incarceration. Everyone knew someone who was detained so there were a lot of them about. One woman I interviewed, whose son was interned at Long Kesh, took one out of her cupboard and gave it to me.

“Here,” she said, “You take it with you back to America.”

“I couldn’t possibly take it!” I protested, “It must be so precious to you.”

“Precious?” she said, “I’ve got these coming out of my ears! I wish my boy would learn to carve something else for a change. Like a statue of the Virgin Mary or a lamp stand!” So she wrapped up the harp and insisted, rather overenthusiastically I thought, that I take it with me.

One day a call came in to NICRA about a shooting in the Divis Flats area – something that wasn’t all that uncommon in those days – and I went out to interview a woman in one of the tower blocks who’d witnessed it.

She was in her mid-thirties, delicate looking, nervous and very quietly spoken. She invited me in for the inevitable tea and biscuits, and I turned on my tape recorder.

“There was a lot of shooting that day,” she said. “There were army snipers on the roofs of the flats. I’d gone out to do my shopping, but when I was walking back, I was told not to go on because there’d been a lot of gunfire. So I waited. After a while it died down and someone said I could probably go on home now; but that I should walk on the far side of the street so the army could see I was a woman.”

She had started to walk along the street when she heard the crackle of gunfire. A boy “of about twelve”, she said, stumbled into her path.

“Help me missus!” he’d cried, “I’m shot!” He’d seemed fine. There was no blood, though he seemed to be in shock.

“Ach, you’re not,” she told him.

“Help me,” he said again.

“You’re alright,” she reassured him.

He fell then, onto his knees and then onto the ground. He rolled on his side. He was wearing a bomber jacket, she remembered, and as he rolled she saw that the back of it was soaked in blood.

“His back was in pieces,” she said. An ambulance was called and she held his hand until it came.

“Am I dying?” he asked her.

“Ach, of course you’re not,” she assured him.

“I think I’m dying.”

“Ach, you’re not. You’ll be alright.”

But he wasn’t. He died before the ambulance got there.

“Was he armed?” I had to ask.

“No,” she said, thinking this a very odd question, “He was a boy. Maybe twelve years old.” But the army would say he was.

I still have the tape of that conversation. But I haven’t been able to bear listening to it for thirty-five years.

By the time I’d finished my tea, gunfire had started to crackle outside. “I’ll make another pot of tea,” she said quietly, “I don’t think you should go out till that stops.” So we had another cup of tea. And then another.

By the time I got back to the NICRA office it was closed and I knew I’d have to use the key they’d given me. When I turned the corner into Marquis Street, there was an army foot patrol there: soldiers standing, as always, with fingers on the triggers of their SLRs . I felt decidedly nervous, something I’d never felt before, given the ubiquity of troops on the streets.

I went to the door and put the key in the lock, anxious to get in as quickly as I could. But, it was a tricky lock at the best of times and I just couldn’t get it open.

After awhile, one of the soldiers came over and offered to help me. I didn’t know what else to do, so I let him. I found myself looking into his face, seeing something other than a gun and a flak jacket for the first time. He couldn’t have been more than eighteen, the same age I was. He might have had to run a razor over his upper lip and chin a few times a week, but his jaw line and cheeks were virgin territory. He even had a few teenage pimples and his face seemed strangely soft.

Why are you here? I wanted to ask. I was mystified. Why aren’t you back in your hometown trying to meet the eye of a girl you fancy across a crowded disco? Getting too drunk on a Saturday night and ending up waking up on the park bench where your mates left you? Sweating over some exam or learning a trade? Falling in love?

He got the door open and handed me the key.

“Thank you,” I said. He smiled and looked away, almost shy. I went inside. And bolted the door.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on "Post a Comment" below.

3 comments:

MORE!!!!!!!!!!!

keep writing donna you really do have a gift for it,its like when i read a good book and feel as though im in it!!!!!

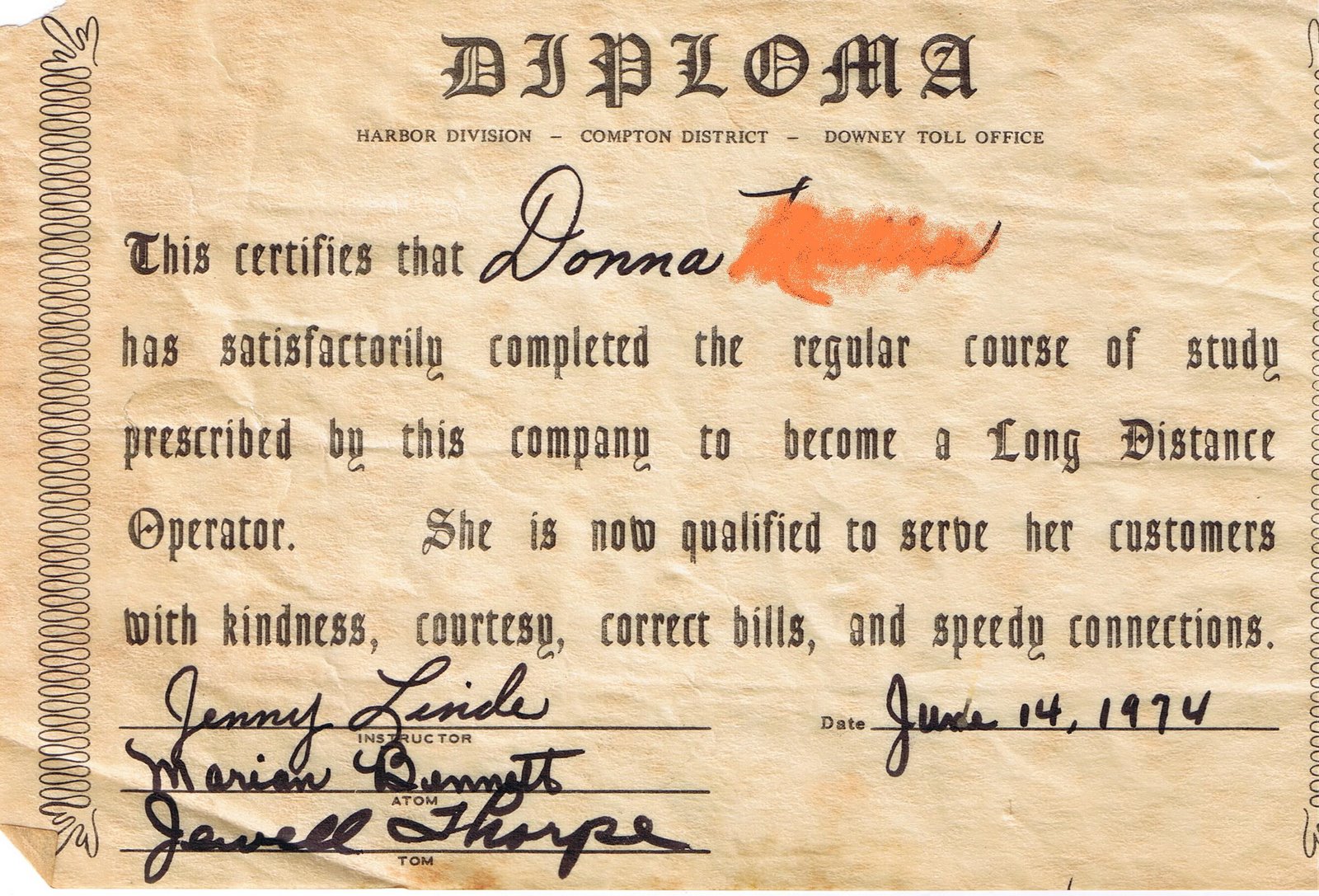

Hey donna, great stories! But the picture "A Saracen crashes through a "Barricade" is actually a Humber Pig. Keep on writing...

Rowland

I bow to what I assume is your greater knowledge.

Post a Comment