I was born in Chicago at the ragged end of the baby boom in 1953. My mother's family were dirt poor and her father lost almost all of his farm in the Depression, except for the bit he kept as a market garden growing vegetables for his family and sweet corn which he sold at a stall on the roadside. My mother was a bright child, and a schoolteacher came to see my grandmother to tell her she should be allowed to continue her education and go to college. My grandfather was totally opposed to this, but my grandmother, who had had to leave school at fifteen to support her mother and disabled sister, defied him on the issue as she did on every other issue. And somehow, with the help of a scholarship, my mother went oft to study at the University of Illinois.

For my mother, this was the door to opportunity, but also to her downfall. For it was there she met a handsome artist from a wealthy Chicago family, who was studying architecture and could dance like a dream. He was the family renegade and I think there was an element of rebellion in bringing my mother, a poor Irish Catholic, home to meet his family.

His mother and father had emigrated from Sweden and had built a small business empire on Scandanavian furniture and property rentals. They had a number of nice houses in Skokie which they rented out to nice middle-class families, and were also, unashamedly, slumlords. The family prided themselves on their sophistication; his mother was a sculptress, and after family dinners, my mother said, they would play string quartets in the living room. My mother, who was studying accountancy and who valued artistic talent more than anything, was rapt.

The Second World War intervened, however, and the man who could dance like a dream joined the Navy and served in the South Pacific on the USS Pensacola, an unlucky ship that was hit repeatedly during the war (and, to complete its bad fortune, was sent to Bikini Atoll to guard the area of the first nuclear tests afterwards). Following a serious hit, the ship was returned to port for repairs at Mare Island near San Francisco. My mother got on a train to meet him there and, in a hastily arranged ceremony at the base chapel and wearing a borrowed wedding dress, she married him. My father shipped out four days later.

As the war was ending, the ship was hit again and again by kamikaze pilots. In one raid, his best friend, who he had been standing next to at the time, was incinerated. My father did not return from the war the same man who had left. Maybe none of them do.

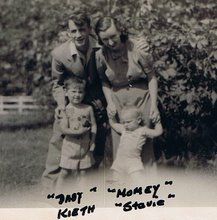

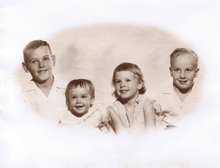

They settled in Chicago and had four children in six years. My father was drinking heavily and couldn't hang onto money. "If he had five dollars in his pocket," my mother would say, "he would spend ten." He could still dance like a dream, but now he was dancing with women who were not my mother - and doing a lot else with them besides. He and my mother would split up every couple of years. But they were crazy about each other and my father would always come back. And make her pregnant again. And then feel compelled to stray. When he was not drinking, my father was warm, funny and charming. He would be unable to stop working or to sleep because he was on top of the world. Other times his moods were dark. He would drink and change, Dr.Jekyll like, into someone my mother didn't know. What she didn't realise until my brother was diagnosed many years later, was that my father was suffering a bipolar illness; manic depression as it was then called. But it was never spoken of. These things didn't happen to respectable people.

His mood swings went untreated and, as my aunt confessed to me after my mother's death, he became abusive to her. And violent. One day my four year old brother told my mother that, when he was grown up he would be able to hit a mommy as well. Still desperately in love with the man my father was when he was sober, she nertheless knew that this could not go on.

A few months before I was born, my father moved out of the family home, which was owned by the Swedish property empire that was his mother and father. He had a girlfriend, a woman who owned a bar and who didn't give him a hard time about his drinking, mainly because she was an alcoholic herself. Although my father apparently saw their liaison as a casual affair, as he was still in love with my mother, things got rather complicated when the girlfriend got pregnant. His mother was horrified of scandal and insisted that my father divorce my mother so that he could marry the girlfriend before she gave birth. When he refused she threatened to cut him off, and that seems to have persuaded him. It is painful to say it, but my father was a weak man. Unlike his mother who had never suffered from sentimentality.

When my father was about nine, his mother found his wild behaviour intolerable, and sent him to a childless couple in Iowa to be adopted. They loved my father and he loved them and he settled well there. But three years later, before the adoption was final, his mother changed her mind and took him back. As far as I know he never saw them again. His sister once described her mother to me as "A very good mother. She just had no maternal instinct."

Since my mother was Catholic and bound by her religion not to get a divorce, the problem now was how my father could achieve one in time to marry his girlfriend as his mother had ordered.

It was the dead of winter, snowing and ten below zero when my mother came to the door of our Skokie house to find a heating engineer, employed by her landlords (the in-laws!), come to service the boiler. After bangng around for a bit, he pronounced the boiler in need of repair. He turned it off and promised to return shortly with the needed parts. He left and didn't return. My mother, smelling a rat, gathered up her four small children and moved into her mother's place, proclaiming that she would not come back until it was sorted. My father then sued for divorce on the grounds of my mother's desertion from the marital home.

It was a messy divorce by all accounts. My mother, contesting it, sat with her Church appointed lawyer; and on the other side were four lawyers who worked for my father's family business. All my father's assets were moved to other members of the family and my mother got no alimony and only a pittance in child support. Within a couple of years, that would dry up too.

My father married his girlfriend and they had a daughter. Another daughter followed a couple years later. They split up some years later and my father's mother, thinking the bar-owning daughter-in-law was unfit to raise children and my father unsuitable, got custody of his two daughters. Finding them troublesome, as she had found my father before him, she put them in a children's home eighteen months later where they languished until my father's death, at the age of 44, in 1967.

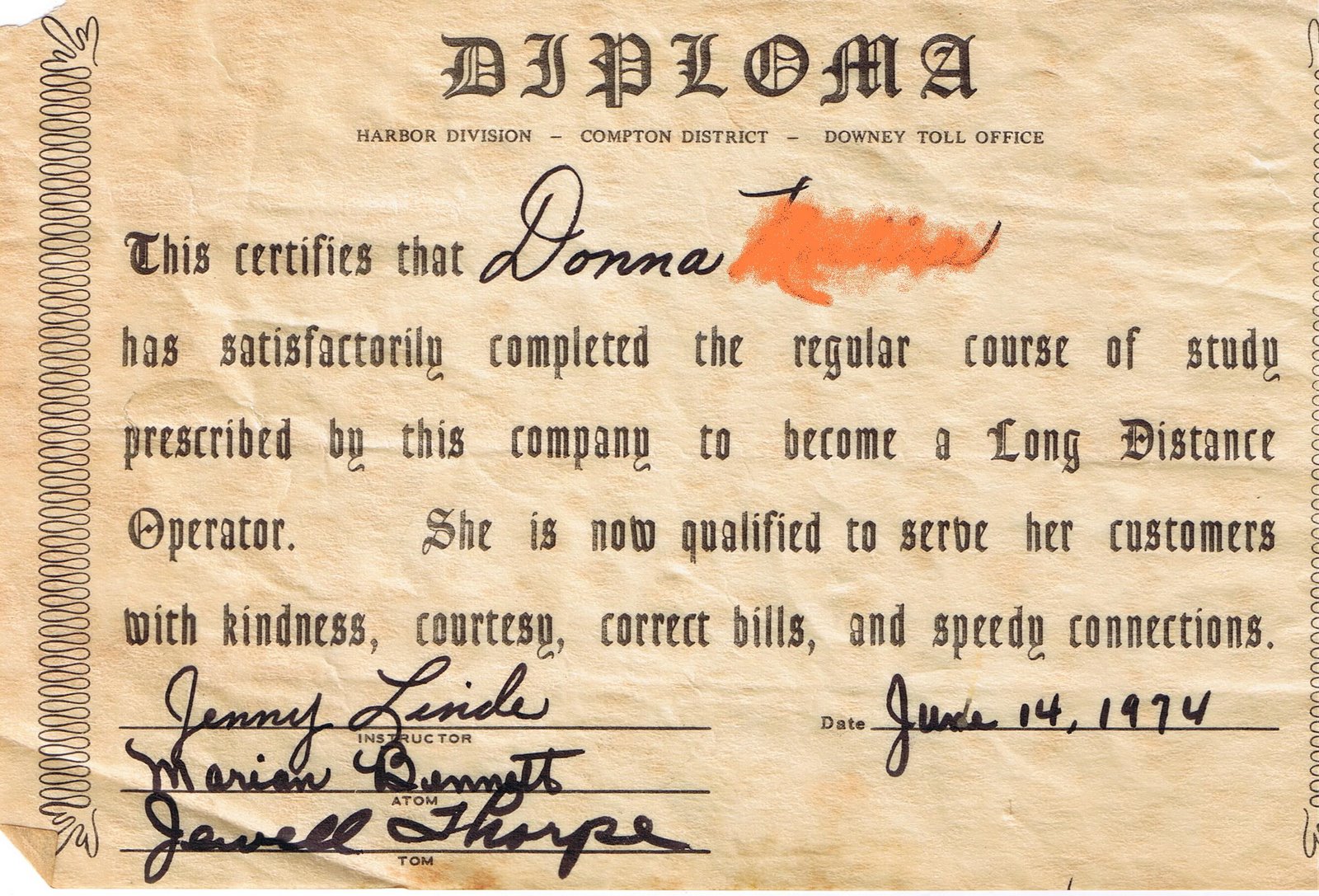

Despite the ideal of the stay-at-home mother of the 1950s, my mother had to go back to work when I was six weeks old. We lived with her mother, my sainted grandmother who took over the mother role, and my disabled great auntie who talked constantly to herself in whispers which, cruelly, my brothers and sister and I found exceptionally funny. But my grandmother's house was small and, when I was two and a half, we all moved to California so that my mother could be near her sister and brother. My grandmother sold her house so that my mother could buy one big enough for all of us.

But, despite her heroic efforts to keep the seven of us in clothes and food and under a roof, she was broken. She slid into a catastrophic depression from which she never fully recovered and used to walk up and down the railway tracks behind our house trying to get up the courage to throw herself in front of a train. And even though I could not have been consciously aware of it at the time, I can't hear a train whistle at night now without a shudder.

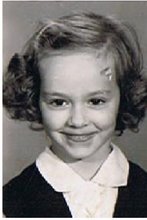

Her dark and desperate moods coloured my childhood. She had no interest in cuddling me as a baby. And as I grew to bond with my grandmother, running to her and not my mother when I was hurt, my mother became more and more resentful. She took little interest in whether I brushed my teeth or was clean when I went to school. I remember streaks of dirt down my arm and my classmates laughing at me because I had "cooties". The worst thing the boys could do to another boy they wanted to victimise was to overpower him, drag him to me and force him to touch me.

Isolated and desperate and seeking some sort of escape, I swallowed a bottle of children's aspirin at the age of eight. Of course I only made myself sick (inexplicably to my family who I hadn't told!) and decided maybe I wouldn't try that again. There had to be another way to escape.

And there was. A magical one.

If you would like to comment on this post, please click on the word "Comments" below.